On several occasions, I’ve pointed out that even if two motorcyclists travel the exact same route, they won’t have the exact same trip. The bikers will have different adventures, meet different people. Riding Route 66 here in the States might be more than a tad common, but each traveler will have his or her own experience, even if that experience is in the cases of Geoff Hill and Billy Connolly their respective usual shtick. Hill, at least, is amusing.

But what if the rider is trying to recreate someone else’s trip: go to the same places; look up and meet the same people? Is that traveler indulging in a sort of hero-worship or an odd form of stalking? Is that traveler trying to expand or deepen an understanding of the original trip or trying to have the same life experience as the original traveler? Or, as William Shatner once observed about Trekkies, is it that such travelers need to get a life?

Paul Theroux, who sees travelers as ghosts upon the road (to use Eric Andersen’s phrase), muses at the beginning of Ghost Train to the Eastern Star (2008) that recreating a trip is “a serious enterprise, but the sort of trip that younger, opportunistic punks often take to make a book and get famous”.

Ghost Train is Theroux’s recreation of his trip some thirty odd years before in The Great Railway Bazaar (1975). It takes a perverse genius to be one’s own “younger, opportunistic punk”, and Theroux compounds the agony (or self-abuse) with a learned footnote: “The list is very long and includes travelers’ books in the footsteps of Graham Greene, George Orwell, Robert Lewis Stevenson, Leonard Woolf, Joseph Conrad, Mr. Kurtz, H.M. Stanley, Leopold Bloom, Saint Paul, Basho, Jesus, and Buddha”.

Obviously the list is representative, not complete. My favorite of this type of book is Peter Hopkirk’s delicious, if shallow, Quest for Kim (1997), which retraces Rudyard Kipling’s titular character’s travels around India and Pakistan.

Motorcycle travel is not immune to this practice. Mark Richardson explains in Zen and Now (2008), a narrative about his retracing Robert Pirsig’s Minneapolis to San Francisco motorcycle trip in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974), it’s a route well-retravelled by. It seems that so many people have recreated the trip, following the route, looking up the same people and places Pirsig, his son, and his friends did, that they are known as “Pirsig Pilgrims” to the people whom they seek out, among others. Richardson incidentally used the trip to gather further insights into Pirsig’s philosophy of quality. He hoped some of the book’s “lessons [would] rub off along the way”.

At least Pirsig completed his trip on two wheels, which is more than can be said for Ernesto “Che” Guevara with his tour of South America. The motorcycle died in Chile, even though Guevara and his great friend and traveling companion, Alberto Granado, carried on by any means possible. That the Norton didn’t make it hasn’t stopped others from retracing the trip on motorcycles from start to finish. At least two have even published their adventures: Patrick Symmes with Chasing Che (2000) and Stephen E. Holmes with To Infinity and Beyond (2011).

Guevara is what is called a controversial figure. Controversial in this context means that when a subject is mentioned people start shouting about what they think about the subject and why what they think you think is wrong, usually in a mixture of clichés and curse words. As a result, although I only have about six thousand words here to save the world, I’ll have to take a step back and quickly address some secondary and tertiary topics.

Let’s start with two people: Che Guevara and Ernesto Guevara. It is cruel, but accurate, to say at this point that Che is the face that launched a thousand T-shirt designs while Ernesto was a living, breathing human being. It’s one of those odd ironies of history that some of his longevity as a brand and a symbol can be credited to an economic system he opposed. Those interested in his posthumous adventures in marketing may find Michael Casey’s Che’s Afterlife (2009) indispensable and a good read.

Actually at the time of the motorcycle trip, Guevara wasn’t even using Che as a nickname. Fúser seems to have been favored. He was a medical student, taking a semester off. Outside of the predictable textbooks, his reading habits included history, mathematics, archeology, philosophy, psychology, and political science, among other subjects. Favorite writers included Karl Marx, John Keats, Jules Verne, Franz Kafka, Robert Frost, Sigmund Freud, Walt Whitman, Bertrand Russell, William Faulkner, Friedrich Nietzsche, Pablo Neruda, Jean-Paul Sartre, H.G. Welles, and Federico Garcia Llorca. But above all, Guevara loved poetry in general and Latin American poetry in particular.

After he came to the attention of the CIA (around 1958), it produced a report that described Guevara as “fairly intellectual for a Latino”. Actually, that reading list would be “fairly intellectual” for an Anglo. It is however rather typical of aspiring writers of the period.

He came from Argentina’s aristocratic upper classes. A keen chess player, he was also an extreme asthmatic who “overcompensated” by becoming extremely athletic. His nickname – El Furibundo or Fúser – came from his prowess as a rugby union player. Holmes finds Guevara “a bit of a lad. He was a womaniser, he liked motorcycles and, as it turned out, he liked a fight (p.19)”. So much for Fúser Guevara for the moment.

Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1950s was a very different place. But that is true for the rest of the world as well. The old empires were crumbling. Former economic and political colonies were becoming independent or taking up arms to become independent; and the Cold War turned hot with the Korean War (25 June 1950 to 27 July 1953).

And while such multinational neo-imperialism/neo-colonialism ventures as the United Fruit Company (UFC) seemed to be holding strong, opposition was already highly vocal, turning up in everything from Neruda’s La United Fruit Co. (1950) to Gore Vidal’s Dark Green, Bright Red (1950), which creepily anticipates the UFC/USA coup in Guatemala a few years later that convinced Guevara to become a revolutionary.

Because the moment someone says “Che”, someone else thinks “Cuba”: the UFC had a neo-colonial presence there, but it was ultimately a distant second to “organized crime”. About the same time Granado and Guevara’s motorcycle called it quits in Chile, Fulgencio Batista staged a military coup, and began turning Cuba into gangster paradise. The mambo was the beat of the Mob. Those interested in Cuba’s rule by “Mobocracy” may find T.J. English’s well-researched, if breezy, Havana Nocturne (2008) indispensable.

Most important, the Pan American Highway had yet to be completed. Although the concept goes back to 1889, by 1950, the only Latin American country that had built its section was Mexico. How much of that was due to simple bureaucracy and how much to the UFC (which has a history of discouraging alternatives to its railroad monopoly) is outside the scope of motorcycle adventure travel books. To be fair, 125 or so years later, the Darién Gap remains, well, a gap in the Pan American Highway.

Of course when dealing with books that have “official” stamps of approval, questions of propaganda arise: how much really happened. That’s a good question with any travel book, actually, regardless of the source. John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley (1962) is probably the best-known question in travel literature. Some of the people and incidents Steinbeck met along the road were faked. A better question might be, why is that asked only when Guevara and the like are involved?

To create a base line to test the validity of Granado’s and Guevara’s reports of their trip, and therefore the trips of Symmes and Holmes, let’s look at another motorcycle traveler who ventured forth into Latin America at about the same time in the early fifties: William Carroll.

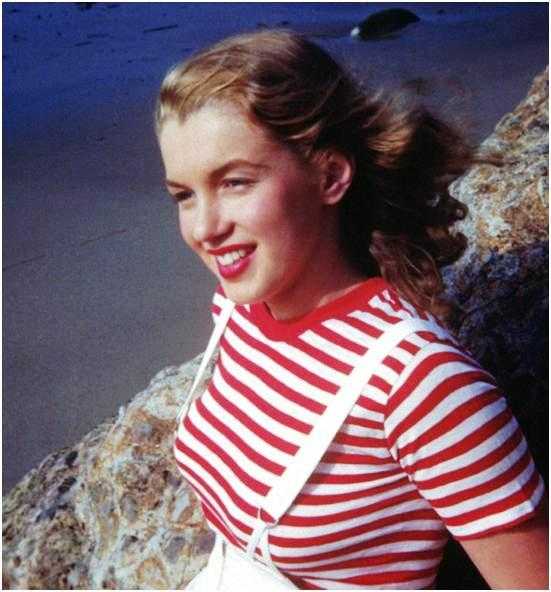

Carroll’s footnote in history may have nothing to do with motorcycles in general or motorcycle adventure travel in particular. It seems that just after World War II he was a professional photographer who ran a film lab. The Los Angeles-based business was doing well, but he wanted to expand. He was looking for a model for what was called a “counter card”.

Then David Conover walked in to get some film developed of a young woman he had photographed. Carroll thought she would be perfect for his counter card and paid her $20 to pose. It was her first paid job. At that point, neither man knew that they had just discovered Marilyn Monroe.

Both Carroll’s and Conover’s photographs were exhibited alongside more famous images of Monroe by Bert Stern, Tom Kelley, and Milton Greene at the 2010 “Becoming Marilyn” show at the Andrew Weiss Gallery in Beverly Hills.

Unlike Monroe, whose life seems to be a bit too well known, Carroll’s is a bit obscure. As near as I can put together, the business seems to have gone south, and Carroll did as well. He packed it all up, closed the shop, hopped on a BSA B33 with his Rolleiflex around his neck and two other cameras in his saddles bags, and on 14 December 1950 crossed the border to Mexico, about a year before Granado and Guevara began their trip north.

Despite the numerous and very real differences between and among the various Latin American countries, they are culturally similar and in some case virtually identical. What Carroll encountered in Latin North America is very close to what Guevara encountered in South America.

Carroll, however, was a very different person, a type of American that was once not uncommon but is now seldom seen: cheerful, low-key, laid-back, self-depreciating, and open for adventure; accepting people and events for what they are or claim to be. Despite having picked up a few magazine assignments (by working his customer network from the photo lab?), he doesn’t look too far beneath the surface. If he had a political idea – right or left – in his head, it would be lonely.

It’s not that Carroll is unaware of the impact of poverty and tourism on the peoples of Latin America, but rather that it doesn’t go much beyond basic observation, as is illustrated in his self-published book, Two Wheels to Panama (1995), which jams 175 black and white photographs of the Latin America that once was into 143 pages. For example, he is fascinated by professional scribes who will type letters and the like for people who cannot read or write themselves, but doesn’t really delve into the levels of illiteracy such full-time employment implies.

In a brief, light, and matter-of-fact style, he covers the usual bribery and bureaucracy, breakdowns and border crossings, not without a wry humor. Because it is the early 1950s, he had to contend with unpaved roads and, in many cases, no roads. He collected a motorcycle license plate from each of the seven countries he visited; learned Spanish on the fly; and spent Easter, Christmas, and New Year’s in strongly Catholic countries.

There’s a drag race with a Harley Davidson, a shooting match with a colonel touchy about his superiority, and a visit to Mayan ruins hidden away on lands controlled by one corporation or another. The Latinos and American ex-pats see him as a “crazy Gringo” not only because he traveled by motorcycle (ultimately some 7,772 miles), but also because his own quixotic acts: giving blood because someone needed it, not because he knew the person or because he was being paid to do it (he refused money).

More interesting from the point of view of Latin America at that time is that he needed permission from multinational corporations to take trains where neither roads nor public transportation were available. Even the Red Cross had to use such rails. While he had a few problems being allowed to use the “privatized” system (more the result of office politics than international politics), his neutral record makes for uncomfortable reading.

Toward the end of Two Wheels, Carroll gives an extensive description of the UFC’s company towns, noting the paternalism, but repeating their explanation of why its way is best. Nevertheless, Carroll points out that not all company town are created equal, and the ones for American ex-pats seem to be better equipped and maintained, but not in those words. He notes (p.122): “Four miles later I had my first view of a banana-company town. Americanized in appearance and neat to the hilt, Palmara differed from a village in the States in its lack of automobiles and the tropics-style housing built on stilts”.

Four pages later, he writes: “To demonstrate the policy of working in harmony with the nation of location, the standard of living for Costa Rican workers had been upgraded in a manner consistent with local economic practices. Golfito’s wages for local labor were high enough to recruit the best workers but not so high as to dislocate Costa Rica’s employment standards. In addition the company had loaned money to private enterprises, which in turn sold their products to the company. Blair’s examples were the rice factories, furniture mill, vegetable gardens and leather tannery. Inter-plantation transportation was by railroad while inside Golfito you walked or owned one of the fifteen automobiles”.

While such brief passages are telling, they are not as significant in terms of Granado’s, Guevara’s, Holmes’s, and Symmes’s trips as Carroll’s photographs. His photojournalistic style, sometimes posed, sometimes composed, let readers see what he saw. More important, it lets readers see something very close to what Granado and Guevara saw. Or dealt with. It’s one thing to read that the roads in Latin America at the time were not paved, or even roads; it’s another to see the evidence.

Carroll’s trip ended in Panama on 4 May 1951. Almost eight months later, Granado and Guevara began theirs. They leave from Córdoba, Argentina, on 29 December 1951 and both kept notes if not actual diaries of their trip.

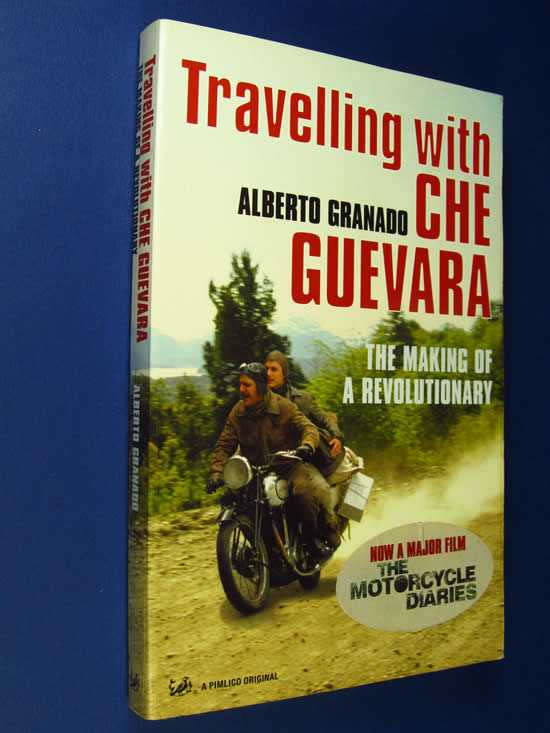

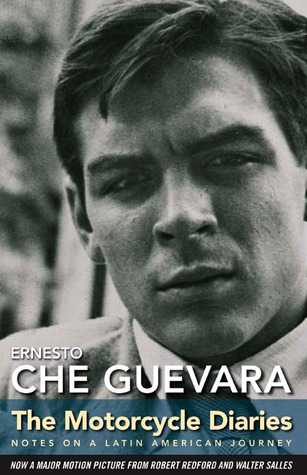

At some point after they returned Guevara reworked his notes into a narrative, which wasn’t found until after Granado had published his diary, Traveling with Che Guevara: The Making of a Revolutionary (1978). About 15 years later, Guevara’s narrative was discovered and published as The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey. Both Guevara and Granado were self-consciously writing “for the record”.

For those who like to find an underdog to root for, Granado may be the best bet. Despite a long and distinguished career in the medical sciences, he will be forever a footnote in history as “that other guy” who traveled with Guevara. Worse, the trip may have been Granado’s in the first place. There are however far far worse fates to befall someone, as Granado, or anyone else in medicine, can explain in great scientific detail.

Granado’s and Guevara’s trip also took about seven months, but covers closer to 10,000 miles, most of which was by means other than their motorcycle, a Norton named Ponderosa II. Granado’s book provides the incidental details of the Ponderosa I. In terms of the route and overall shape and tone of the trip, the two accounts agree. Granado provides more incidents and more detail.

Exaggeration seems to be normal for fish and travel tales (Symmes has a bit of fun with that point). Most differences are close to that old saw about four ounces of water in an eight ounce glass: one person sees it as half full; the other as half empty.

The actual discrepancies are few and minor. The two that obsess Symmes and Holmes are the incident of who saved the cat and the incident of the Uros and the Peruvian lake respectively. Neither seems bothered that a raft used on the Amazon River is called Mambo-Tango in one account and Kon Tikita in the other. (To be fair, Guevara is indulging in a mix of camp and whimsy with Kon Tikita; the reader isn’t expected to take that name seriously.)

The trip was something of a gap year project: Granado was at a loose end; Guevara took a break from medical school. Granado includes the amusing anecdote of being taken aside by Guevara’s mother, who asked him to make sure her son returns to Buenos Aires to finish his medical studies. The twelve-year-old Norton itself was not in top condition, was carrying more weight than it should (two riders, plus baggage), and was traveling on roads that were sometimes not meant for any sort of mechanical transport. I’m probably not the only person in the wacky world of motorcycle adventure travel who wonders how they even made it out of Argentina, never mind well into Chile.

Both books provide a range of set pieces and interesting people, Granado’s more than Guevara’s. But the quality changed after they abandon Ponderosa. As Guevara notes in his poetic and whimsical style, that the two had been, “gentlemen of the road. We belonged to a time-honored aristocracy of wayfarers”. He adds, “It was our last day as ‘motorized bums’; the next stage seemed set to be more difficult, as ‘bums without wheels’” or “just two tramps with packs on our backs, and the grime of the road encrusted in our overalls”.

As wheelless bums they hike, hitch hike, stowaway, and, if they have to, even pay to get from place to place, by bus, by boat, by foot, by raft, by truck, and by airplane. In picking up odd jobs for food and shelter, if not cash, they also had to live as many of the underclass and working class of South America did. Mostly they lived by their wits, scamming free room, board, and transportation whenever and from whomever they could.

Among the more memorable set pieces are a train trip to Machu Picchu; trying to travel as stowaways; coaching soccer for food and shelter; Guevara’s attempts to seduce a woman whose husband objected (followed by a quick exit); and working as volunteer firemen. They became accomplished in finding police stations and guardhouses to crash in and using their medical credentials to stay at clinics and hospitals. A stay at a leprosarium proved to be a peak experience for both of them.

They also visited company towns, mining operations, and archeological sites, drawing various conclusions about life in Latin America. Granado favors traditional Marxist and anti-capitalist analysis, while Guevara, who certainly indulges, also speculates on a single Latin American identity, which he calls Mestizo, primarily a mix of Spanish and Native South American cultures. In strict Spanish the word does not actually carry the connotation of “non-white” that it would in Anglophone culture. That connotation was picked up when the word was adopted into the English language.

Granado’s book was produced for didactic purposes, but the elements of propaganda are obvious and writ small. By the end of the book, the hagiography has taken back seat to the adventure. He knows how to write, but he’s not a writer, which keeps things simple and matter-of-fact. The Marxist analysis is short, making it easy for readers to ignore or go for it. The constant refrain of how this problem or that can be laid to the United States is simplistic even when true – which it is more often than people outside Latin America realize – but usually it’s just plain irrelevant to what is happening.

Never the less, the descriptions of farming and mining (as well as company towns) are virtually identical to Carroll’s. The facts were similar, whether or not an interpretation or analysis was applied.

His continual underscoring of how this anecdote or that illustrates how brilliant Che is or how much the man of action is minimally intrusive for the most part, occasionally irrelevant, and sometimes counterproductive. One time Granado praises Che for sprouting some sort of social nicety typical of his aristocratic background: upper class twit. In another that sort of introduction kills some of the fun of a great anecdote involving a mysterious stranger warning them of danger. It would have been better to have stuck the propaganda in after the punch line.

It’s in this part of Granado’s version that a possible answer to Symmes’s point about the cat lies. Granado is painting a great hero. Heroes can’t be perfect and must be sympathetic. Therefore, Che’s asthma attacks are listed one by one (Guevara only includes the major ones that caused further complications). That he was tone deaf and couldn’t sing becomes something of a minor running gag, as does his lack of skill as a dancer. (Although as an athlete, he was likely to have been a passable if not competent dancer.)

Which bring us back to the cat and who saved the cat from the fire. Granado claims Guevara did; Guevara claims Granado did. Symmes says one of them is “fibbing”. Symmes isn’t just questioning each man’s veracity here, he is also creating a suspense device, a question that implies an answer will be given. (Holmes, a less careful writer, doesn’t follow up with his question.) Symmes tracks Granado down and confronts him. Granado, a gentleman, stands by his written word.

In one of those meaningless coincidences that some call fate and others conspiracy, there is a well-known book on screenwriting called Save the Cat (2005). For the author, Blake Snyder, saving the cat is one of the hallmarks of a good screenplay. He writes: “Because liking the person we go on a journey with is the single most important element in drawing us into a story (xv)”.

Snyder expands on this concept a few lines later: “I call it the “Save the Cat” scene. … It’s the scene where we meet the hero and the hero does something – like saving a cat – that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him”. A more suspenseful question might have been to ask how each writer is using the incident to manipulate the reader.

While Che is the hero of Granado’s narrative, Guevara is the hero of Che’s narrative. He is very conscious of the decision and being very much a writer with an interest in poetry expounds upon the dichotomy: “The person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I am not the person I once was”.

Che is also aware that the reader may take a dialectic approach to his narrative. Using the techniques of photography as a metaphor, he writes, “[I]f I present you with an image and say, for instance, that it was taken at night, you can either believe me, or not; it matters little to me, since if you don’t happen to know the scene I’ve ‘photographed’ in my notes, it will be hard for you to find an alternative to the truth I’m about to tell”. Granado, of course, turned out to be that alternative.

Che reworked his notes about a decade after the trip. To assert something without fear and without research, in places it reads as if it were a draft for a longer, more developed piece. Motorcycle Diaries is half the length of Traveling with Che, and repeats perhaps a third of the incidents. He includes more of scams, including the ones that didn’t quite work and even one where they were scammed and were left by the side of the road one night.

Che presents himself as a more scholarly, but less admirable person, even though he was consciously creating his own myth despite the well-known Marxist objections to cults of personality. At this point, though, any relationship between what he had in mind and the free-floating icon may be regarded as purely coincidental. The impression I was left with was of someone trying to create a poetic narrative as much as a political one.

Both men present the trip as what made Che a revolutionary, a point that Symmes picks up in Chasing Che. In addition to teaching journalism at New York University, Symmes is a contributing editor to such publications as Outside and Condé Nast Traveler. He followed up with The Boys from Dolores (2007), which looks at the lives of Fidel Castro’s fellow graduates from the Colegio de Dolores, a prestigious Jesuit academy, which educated the ruling class to maintain their rule. Most of Castro’s classmates left Cuba during or after the revolution, never to return. Latin America in general and Cuba in particular has become Symmes’s specialty, although he is also a well-respected science writer.

About a decade before Dolores was published, Symmes felt the need to understand Che, to find out what motivated him, and to sort out his legacy, political as well as iconic. Symmes more than just accepts the conventional theory that the motorcycle trip radicalized Che, he openly embraces it. “He was a traveler now, the act of discovery is not merely the basis of travel but is also the quintessential revolutionary act. Every long journey overturns the established order of one’s own life, and all revolutionaries must begin by transforming themselves (p.10)”.

Noting that later trips would be more significant in shaping his character and ideology, the motorcycle trip interested Symmes the most simply because it was the first. Apparently an early jaunt around northern Argentina by motorized bicycle doesn’t count.

Thanks to better roads and a better bike, the actual recreation of the trip takes about four months, but Symmes doesn’t stop there. He went the extra mile – or miles – to visit Bolivia, where Che was executed, and even Cuba itself. It makes for a richer, more layered book.

Symmes also rode a twelve-year-old bike, but his was a blue and orange BMW R80GS. Despite disdaining naming things, the Beemer becomes known as Kooky, for La Cucaracha, the cockroach, which in North America is regarded as a Mexican folk song. Its origins are actually Spanish and go back to the Fifteenth Century, if not earlier. There are many versions of the song. In each, the cockroach can’t go or walk straight for different reasons, often political.

Kooky couldn’t go because it didn’t have gasoline; in the US (or Gringo) version, the cockroach can’t walk straight because it didn’t have anything (alcoholic) to drink; in the Mexican version that Symmes was thinking of, it can’t walk straight because it didn’t have any weed to smoke, an allusion to then President Victoriano Huerta, whom the Villist revolutionaries of 1900-1910 believed never met a substance he couldn’t abuse. Another story is that the cucaracha in that version refers to the American soldiers sent into Mexico at that time.

Symmes finds the song annoying (no argument here, and I was brought up with it) but apparently doesn’t know its revolutionary connections or doesn’t think the connections would interest his readers.

Kooky, if it matters, had issues with altitude and potholes; wiped out in the Andes; and ran out of gas in the pampas. As for Symmes, if being chased by dogs weren’t enough, just about everywhere he stopped, he was asked what sort of bike Kooky is, how fast, how far… the usual barrage of questions traveling ghosts get. Except he’s a journalist and he likes to ask the questions.

His quest for Che proves to be a great conversation opener, especially when he tracks down a place where Che stayed or did something. It’s almost a running gag how fascinated locals are, especially when he pulls out his copy of the book and points out the relevant passages.

Symmes visited the leprosarium Che visited; tracked down the descendants of the German family he stayed with; and located the firehouse where he stayed and, when helping put out a fire, may have saved a cat. The younger firemen were fascinated by the Che connection; the older ones denied everything.

He also tried to live like Che, getting covered by the same newspapers that wrote about Che on his motorcycle trip or an ugly attempt to cadge free drinks. Symmes was on a rather tight budget, but still, as a North American, he was – and would be perceived to be – wealthier than the people he was trying to scam.

While all that is quite jolly in its own way, the strength of the book may be his ability to track down interesting people with interesting stories to tell about Che. There’s a rum-soaked interview with Granado; a more sober and subtle one with Che’s former fiancée who broke off the engagement during the trip (so much for having given her a puppy!); and an odd one with an old revolutionary soldier who had trained under Che in Cuba.

Of course, Symmes has his own adventures: a humiliating one with a Good Samaritan and a charming one with the daughter of a photographer in Cuzco. He was looking for 1952 photographs of the city to see what Che would have seen. (Carroll’s photographs would have been useless for Symmes’s purposes.) He comes away with a more thoughtful and interesting souvenir, the backstory to which might be a book in itself.

There is also an extended interlude at a Chilean utopian preserve run by an eccentric (or visionary) millionaire from the States and a fascinating visit to a prison full of captured Shining Path guerillas. Symmes also covers the site of Che’s execution where he discovered it had become a minor tourist attraction.

Chasing Che is helped by his trip coinciding with the discovery of Che’s remains. The return of the remains to Cuba provides an appropriate and compelling conclusion to the book.

Because Symmes is a journalist, not a novelist, the reader gets more about what he observed and uncovered and less about him and his reactions. There is no sense that the trip may have changed him in any substantive way. Nor does there seem to be have been any real change in his feelings or opinions about Che. Symmes never seems to have liked Che very much, noting his arrogance and brutality at every turn, which makes me wonder why he started out retracing Che’s steps in the first place. His conclusion that Che’s legacy is more as an iconic symbol than as any actual political change or achievement is certainly valid.

No one can accuse Holmes of being a professional journalist. For the first half of To Infinity even writer might be pushing it. Then his narrative abruptly goes from readable to fascinating.

Holmes reunited with his old band mate, Peter Sandford, after some 30 years. Sandford saw The Motorcycle Diaries and was inspired. They would recreate Che’s trip. Not only that but on 1939 Nortons. Could it have been done? Would they be able to do it? Or as the subtitle blares: “What Che Guevara Started, Someone Had to Finish”.

This is not the most pressing question one can ask about Guevara and his legacy as Che. It’s a glorified bar bet. It’s the stunt of the week on Top Gear.

What Che started, or tried to start, was a revolution to kick “Yankee imperialists” out and create a Latin America for Latin Americans (Mestizos). His journey actually ended in Bolivia years later, with his all but ordering one of his military captors to stop drinking and kill him.

Worse, Holmes and Sandford were not just following in Che’s footsteps, but also Symmes, whose book had been published barely a decade earlier. And Chasing Che should be on everyone’s list of top ten motorcycle adventure travel books.

But wait, there’s more (as they say on late-night television ads). On page 45, Holmes asserts no one had attempted the trip since 1952, that Granado and Guevara left in late December 1951 notwithstanding. Also notwithstanding are Chris Scott’s admonitions about attempting long distance travel with vintage motorcycles. The more than seventy-year-old vehicles turn out to be both their passports to adventure and their letters of introduction.

Unlike many bar bets, Holmes and Sandford had a lot going for them. Any 1939 Norton still running in the 21st Century would have been much better maintained than the Ponderosa II (and would have had better access to replacement parts and skilled mechanics when necessary). Since each man would have his own bike, neither would be overloaded, let alone as overloaded. Furthermore, the roads were in better condition.

Holmes and Sandford quickly found their Nortons and respective kits through a mix of Euro jumbles and online auctions. Holmes went for his concept of a period look for his kit, the results making him look like “a real Rocker (p.27)”. The voyage got named (Revolution Road) and a web site was established. Despite pushing 50, Holmes is a child of today. Eventually they mastered pre-standard controls and named their bikes: Holmes’s is Kate, after the model Kate Moss; Sandford’s, Cacafuego, which is one of the better bike names I’ve encountered.

For the first hundred pages or so, the narrative follows Holmes and Sandford’s recreating Che’s trip with some obvious changes and asides. They failed to meet Granado (at the time of their trip, he would have only a couple of years more to live) and found the mines that Holmes feels is the number one reason Guevara the medical student became Che the revolutionary closed. The Chilean firehouse not only acknowledged Che slept there, but even gave the two a quick tour of the actual room. Had Holmes been aware of Symmes’s completely different experience, this could have been a deeper or richer anecdote.

They evade talking about the Falklands in Argentina and deal with Hells Angels in Columbia. Mostly they deal with questions about the Nortons and the trip: what is it; how old; how fast; where are you going; where are you from? Unlike Che and Symmes, Holmes and Sandford didn’t have to bluff or bully anyone for publicity. The Nortons did it for them. They wound up on Chilean and Argentine television, as well as the same paper that covered Che and Symmes (and who knows how many other Che pilgrims over the years). They even get to meet the man who built and restored the Nortons used in the movie.

Holmes and Sandford live off a diet of chicken and chips, broken up by an encounter with barbequed goat’s testes and the ultimate danger: dinner at place called Machu Pizza Restaurante.

The book rolls along with a hundred or so readable if forgettable pages. There are people who are interesting without being compelling; set pieces that are pleasing without being astounding. Then they get to Peru and it’s as if someone finally hit the kickstart. Interesting people compete with interesting adventures (including the one that gives the book its title), all but making their crossing Peru one long set piece.

There is a Norton tavern in Cusco for ex-pats and vintage motorcycle enthusiasts. The American owner, Jeff, once rode his 1974 Norton Commando to Ushuaia and back. There is a visit to Machu Picchu; Nineteenth Century boats and buildings (including Gustave Eiffel’s Casa de Fierro); and an orphanage with 600 children. Greedy boat captains, good Samaritans who know how to drive hard bargains, and amorphous borders contribute their parts.

To Infinity is not the book to read for insights or observations about contemporary Latin America. It’s not that Holmes is blind to some of the issues. He does write at the beginning of the book: “The five capital cities of the countries we passed through are like any modern cities in the world, but they mask the endemic poverty that is rife in all five countries (x)”. But such observations are few and in passing. For any sort of historic or contemporary analysis, Symmes is far superior.

Holmes’s descriptions border on the travel brochure. He writes San Telmo “is characterized by colonial buildings, cafés, tango parlours and antique shops, which line the cobblestone streets. Filled with artists and dancers, the main square, Plaza Dorrego, hosts a semi-permanent antique fair and tango-related activities for both locals and tourists and has a real Bohemian feel to it (p.35)”. That’s not a description, that’s a checklist for a tourist trap.

Awesome, a meaningless adjective, is used to describe a stretch of the Andes (p.81) and a superliner (p.90). Awesome. While “the night was still young – unfortunately we weren’t” may have been funny on page 61, but isn’t when it’s repeated on page 107. Nor is it awesome.

To be fair, To Infinity is meant to be light reading, and it’s certainly that, but the Peruvian sections indicates it could have been a bit more.

Because Chasing Che targets a mainstream audience a lot of the usual elements of a motorcycle adventure travel book are muted, which is to say it’s more about destination than transportation, reflection as much as reportage, a sense of the world in its complexity outside of motorcycling. Readers who enjoy Lois Pryce will probably like Symmes. The intents are more serious and the results more literary. To Infinity and Beyond is much more the traditional motorcycle adventure travel book and will appeal to readers more interested in the usual motorcycling elements.

Similar distinctions can be made between Granado and Guevara. Traveling with Che is more about the how of transportation, while Motorcycle Diaries is more about reflection, if not analysis. Granado has the better translator and explanatory footnotes. Guevara’s is weaker and the footnotes often inadequate. When Guevara humorously says he took Gardel’s advice and turned north, the footnote needs to explain to the reader why and where Carlos Gardel made the original suggestion. A footnote about a character in José Hernández’s Martin Fierro is out and out useless, especially for those unfamiliar with Latin American literature. Readers who simply want a checklist of what happened on the original trip might do better with Granado. Or just download the movie.

Two Wheels to Panama is one of those obscure treasures that appeal to serious readers or collectors of older, lesser-known motorcycle adventure travel narratives – Pryce, say, or Sam Manicom. It’s a quick, enjoyable read and the photographs are wonderful. Like Chasing Che, Zen and Now has more serious intent – and results – but would most likely appeal to readers who are Pirsig fans if not pilgrims, aspiring or otherwise.

Given Theroux’s position in the “revolution” in travel writing in the 1970s, all of his travel books are required for readers interested in the genre in general and those interested in writing travel in particular. Ghost Train is as good a place to start as any. While designed to stand alone, reading (or remembering) Railroad Bazaar may be helpful.

Neither Che’s Afterlife nor Havana Nocturne have much to do with motorcycles, let alone motorcycle adventure travel. The latter is more accessible, an easy, true crime narrative, while the former, by looking at Che as an exercise in branding, might appeal more to those with such specialized interests outside of motorcycling as marketing. For a proper appraisal of Che’s life (if not legacy), there is Jon Lee Anderson’s Che: Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (1997), which is widely regarded as definitive.

Quest for Kim is perhaps best for those interested in Kim, Kipling, or “the Great Game”, in my case the first. While my friends growing up all wanted to be James Bond, I wanted to be Kimball O’Hara. I was weird even then. Save the Cat is best for those interested in writing screenplays.

As for Che himself, it would be an amusing irony of history if the Soviet Apparat got it right when it dissed him and dismissed him as an “infantile adventurer”. Just another hungry ghost, a rider upon an endless road.

Jonathan Boorstein

jonathanb@theridersdigest.co.uk