Sometimes I think my life is ruled by synchronicity.

Synchronicity is a concept developed by Carl Gustav Jung in the 1920s, although he didn’t devote an entire paper to the subject until 1952. Synchronicity is a sort of pointed serendipity. It is seeing or experiencing a relationship or meaningful coincidence between or among a number of events or objects. Although the connections are made by meaning, causality is not excluded. Meaning may be provided internally or externally.

In this case, synchronicity took the form of the black leather jacket. The experience felt less like serendipity and more like stalking.

To begin with there was, Motorcycle Cultures: Fashioning Bikes, Building Identities, an exhibition at The Triangle Space of the Chelsea College of Art and Design that accompanied the recent conference of the International Journal of Motorcycle Studies (IJMS), covered in the last issue (181) by The Rider’s Digest editor and Fearless Leader Dave Gurman (The Clever Girls and Boys’ Club).

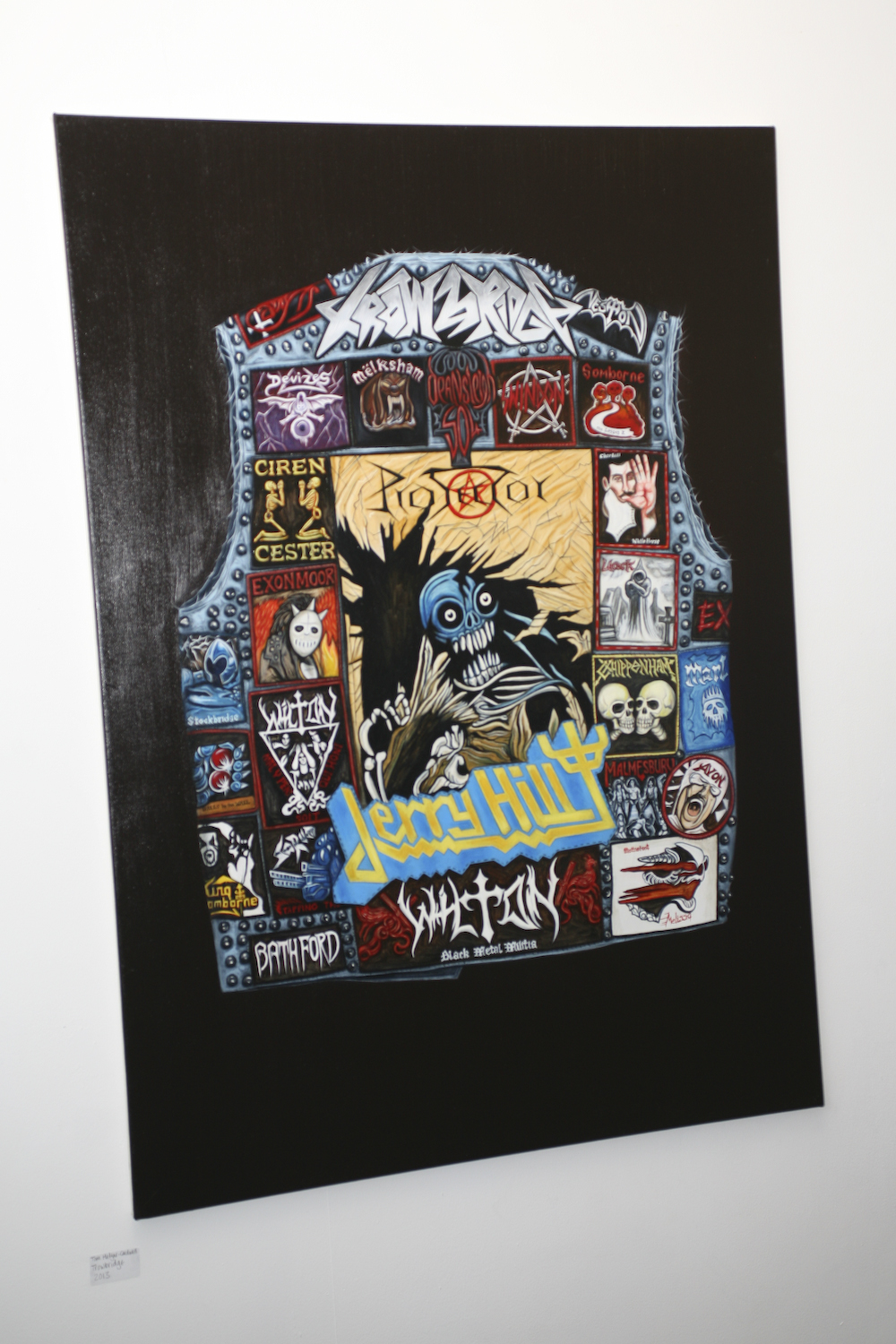

One of the artists whose work created a buzz here at The Digest was Tom Helyar-Cardwell, whose Battle Jacket project analyzes and interprets the customization of the black leather jacket in terms of popular, personal and political iconography, as well as its roots in heraldic and military traditions through his art work. The project includes the customized decoration of ‘rocker’ and ‘metal head’ jackets as well.

The black leather jacket also played a small part in the summer exhibition Punk: Chaos to Couture at The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. The show was less than successful, but the jacket’s place as desiderata for proper Punk dress was noted: at least in passing.

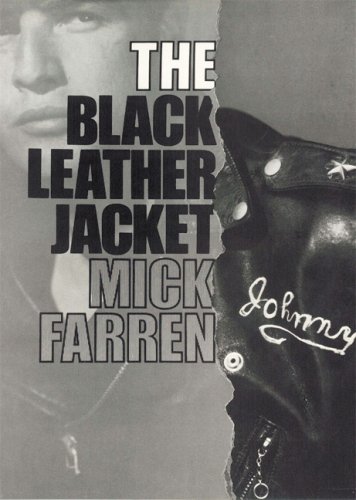

In addition, Mick Farren died. He was more than just a professional provocateur in his career as a writer, activist and performer, his social history of the black leather jacket has become as much a classic as the jacket itself.

That led me to go to get my copy of The Black Leather Jacket (1985) off the shelf, only to discover Farren’s book was but one of more than a dozen volumes on the topic I had picked up over the years. As for jackets and their customization, Farren himself also observes: “Bike jacket decoration became the new heraldry” (54). Noting the parallel between the leather jacket and medieval armor, he says, “The armour confers both a purpose and an identity” (p.18).

And last and definitely least, I had to take my black leather jacket to the tailor to replace a torn pocket. He conceded that a 15-year-old jacket probably did not need to be cleaned as well. Or at least there was no way I’d have it cleaned.

Of course, all that may just be apophenia (seeing connections where there aren’t any).

There is nothing apophenic about the ubiquity of the black leather jacket. It is as much a staple of a complete wardrobe as the little black dress or the navy blue blazer. It can be as quintessential as a Schott Perfecto or as ‘this year’ as what’s on a fashion week catwalk. “Together with jeans and T-shirts, the leather jacket has managed to establish itself as one of the cult items in the contemporary wardrobe,” observes Anne-Laure Quilleriet (p.9) in The Leather Book (2004), which has a picture of the Perfecto on the cover.

“What makes the Perfecto The Real Thing is its Bad Boy/Girl, wrong-side-of-the-tracks image. That and the fact that it is a classic, anti-fashion garment, virtually unchanged in its design for some five decades,” Ted Polhemus points out in Street Style (p.11). Street Style (1994), the catalogue from an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, documents forty different street styles since 1940. Close to half of them include a basic black leather jacket as a way to identify a lifestyle, if not mark territory or assert authenticity.

In an article in the IJMS, Marilyn DeLong, Kelly Gage, Juyeon Park, and Monica Sklar conclude that “The black leather jacket remains the ‘go-to’ uniform of bikers”. They add, “[Bikers] find their black leather jacket provides them with an ability to move between their various life roles” (From Renegade to Regular Joe: The Black Leather Jacket’s Values for Bikers, Volume 6, Issue 2: Fall 2010).

While DeLong, Gage, Park, and Sklar point out that there is more to wearing a black leather jacket than just the protection it provides, they shy away from addressing the near-sacred status it has with some riders.

After all, “Riders who do select gear for practical reasons are more likely, however, to order a Darien jacket made of 500 denier Cordura Gore Tex with a fleece lining and Scotchlite reflective tape in hi-viz lime yellow, or a BMW Motorrad Club Jacket made of rugged polyamide impregnated for water resistance with removable safety armour in the elbows and shoulders. Modern fabrics – more lightweight, durable and waterproof – have supplanted leather for rider protection,” (p.181) Steven E. Alford and Suzanne Ferris point out in Motorcycle (2007).

A close analogy of the significance of the black leather jacket might be the belt of a martial artist. Tradition has it that the belt holds the martial artist’s rank, power, and knowledge. The color, the bars (patches) sewn on, how worn it is, are the martial artist’s history, if not his or her résumé. The belt (unlike the uniform or gi) is never washed or cleaned, lest that power and knowledge be washed away. Tying the belt on is a near sacred, almost ritualistic assumption of that identity.

While the black leather jacket isn’t quite that layered with significance, it comes close. It protects and projects the rider, a mix of personal safety and public billboard. It’s a résumé of who the rider is in style, scratches, and scruff marks.

Quilleriet quotes couturier Jean Colonna as saying, “In a black leather jacket it is easy to pick out the fakers. The jacket is there to protect you and to say who you are” (p.337). She observes about Colonna, “A biker himself, he had no qualms about scuffing jackets with sand paper and putting them in the washing machine” (p.336).

That aspect of the black leather jacket has been noted by others as well. Polhemus quotes Johnny Stuart: “The fancy fashionable versions of the Perfecto which you see all over the place these days water down the significance of the thing, taking away its original magic, castrating it” (p.12).

The lost magic is authenticity. Polhemus observes, “If today more and more people use their dress style to assert ‘I am authentic,’ it is simply evidence of our hunger for the genuine article in an age which sees to so many to the one of simulation and hype” (p.7).

Going from subversion to submission, from outsider to insider, in less than seventy years is quite an arc for an item of clothing that didn’t even exist before World War I. Farren notes, “The black leather jacket has always been the uniform of the bad. Hitler’s Gestapo, the Hell’s Angels, the Black Panthers, Punk rockers, gay bar cruisers, rock ‘n’ roll animals and the hardcore mutations of the eighties, all adopted it as their own” (p.12).

It went from the military to the militant, from street to chic. “It has been a comforting companion to first motorists and aviation heroes, a manly symbol for bikers and thoughts, and a powerful erotic armor for fetishists,” Quilleriet adds (p.8).

Some want to trace the origins of the black leather jacket to prehistoric cave dwellers dressing themselves in animal skins, which is a bit like Pooh-Bah tracing his ancestry to the primeval ooze.

More common is to trace the leather jacket back to the buckskin jackets of the American Wild West. This historic line goes as far as to see the origins of mixing denim and leather as well. It seems about as likely as saying the origins were in the leather waistcoats worn for warmth in Spain even earlier in the nineteenth century, a point curious enough that the Duke of Wellington commented on it to Philip Stanhope years later (1836).

Another slightly odd choice for the origins of the jacket is in lederhosen, a form of male dress I find less amusing than most having been traumatized as a child at Christmas dinners in German restaurants by oom-pah bands playing Silent Night.

While the relationship between leather jackets and leather trousers falls somewhere between obscure and non-existent, the theory is at least half right. Alford and Ferris state clearly, “The black motorcycle jacket…originated with German aviators of the First World War, such as Manfred von Ricthofen, the famous Red Baron” (p.181-182). It was developed to keep Germany’s fighter pilots warm in the open cockpits of the warplanes of World War I around 1915.

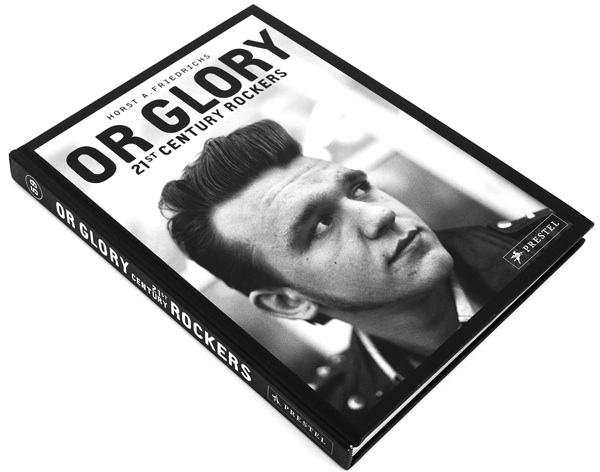

This makes the black leather jacket a year or so shy of its centennial. The original jacket was longer, covering at least the hips, and became standard apparel for dispatch riders as well as aviators. As Derek Harris of Lewis Leathers explains in Or Glory (Horst A. Friedrichs, 2013): “Essentially you’ve got aviators with no cockpits, motorcyclists and drivers of open top cars: the main thing they’ve got in common is the need to keep warm and dry, and leather was obviously a good medium”.

Quilleriet credits an army doctor, Major Malcolm C. Grox, with creating the B3 bomber jacket in the 1930s. A member of the Alaska Corp, he felt restricted by the longer jacket and had it cut off at the waist.

Farren adds, “This combination of dash and democracy must have contributed, at least in part, to the way in which the same leather jacket became the unofficial uniform of the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War” (30). It was also the unofficial uniform of such pioneering ‘aviatrices’ as Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart. (On a less feminist note, they may have also unintentionally pioneered the girls-in-leather fetish.)

Eventually, the back of the bomber jacket became a blank canvas for the pilot to express whatever he held dear or deemed interesting. Emblems, pin-ups, records of hits, all personalized the jacket to its owner.

While the flight/bomber/aviator jacket would continue to embody being one of the good guys, if not virtue, its motorcycling sibling went on a rapid downward spiral, enhanced by the rise of Fascism on the one hand and the film industry on the other. Alford and Ferris note, “Later associations with the Nazis further equated leather (and the colour black) with power and domination” (p.182).

The postwar adventures of the black leather jacket are somewhat better known. As war surplus or souvenir, the leather jacket became a favorite of a range of subcultures that were not obvious fits into the mainstream. Many came from the lower end of the socio-economic scale and became rockers or, earlier, café racers. Here in the States, bikers tended to band together in formal or informal clubs and joined the American Motorcycle Association (AMA). Others formed outlaw gangs. The more brutish (or thuggish) favored Nazi regalia and insignias to annoy and provoke.

Concurrently the black leather jacket became a fetish item for the sexual underground in general and the gay S/M underground in particular. The gay biker clubs of post-World War II California may have organized the gay sadomasochistic underground as well as inspired Santa Monica born-and-bred Kenneth Anger, and perhaps even Tom of Finland.

In their discussion of the black leather jacket as fashion and fetish, Alford and Ferriss quote from Larry Townsend’s Leatherman’s Handbook (1972) to demonstrate the erotic attraction of leather in general and riding kit in particular (p.185). The quote is from the opening paragraph of an entire chapter dedicated to the gay motorcycling scene (The Bike and its Owner, p.143-155).

Townsend writes: “Intrinsic to the leather scene is the motorcycle and the guy who rides it. The clothing we all find so appealing is primarily designed for the cyclist’s use, and the organized in-groups are largely bike groups. There is no disputing the sexual appeal of a leather-clad rider on his great rumbling machine. As a symbol of phallic might the motorcyclist is the epitome, the living embodiment of our fetish” (p.143).

Townsend was an early leader and spokesman for both gay rights and sexual freedom (i.e. sadomasochism). To judge from the motorcycling parts of the chapter, he was a biker at one time himself. Townsend explains the relationship between the organized riding clubs and the eventual organization of the s/m scene, often referred to as leather, and hence the title of the book. The clubs were recognized by the AMA until institutional homophobia drove them away.

It’s little wonder that the gay biker look, whether just for riding or other possibilities, is credited by some for helping establish the gay clone look of the black leather jacket and blue Levis, later adapted by straight boys who wanted to suggest that they might, just might want A Walk on the Wild Side.

It is not known how much Anger knew about the gay biker scene before he left for France in 1947 at the suggestion of Jean Cocteau, who would go on to create his own memorable image of eerie and elegant motorcyclists two years later in Orphée. When Anger returned permanently to the US in the early sixties, he drew upon that sub-culture for his cult classic, Scorpio Rising (1963), which features black-leather-clad bad-boy gay bikers sporting Nazi insignia. The film’s ability to fetishize the leather and the bikes was quickly picked up by bikesploitation movies, carrying the image and the message of the black leather jacket to the mainstream once again.

Unlike the jacket itself, the erotic illustrations of Tom of Finland would have remained within the gay communities had it not been for Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren printing one of the pictures on T-shirts in their commodification of Punk. Tom of Finland began sketching pictures of men in tight-fitting uniforms – military and motorcycle – during the Nazi occupation of Finland. Peaked caps and leather jackets figure as prominently as exaggerated genitalia.

It didn’t take that long for the fetish look to break into the mainstream, epitomized by women in black leather catsuits. In film, the most famous might be Marianne Faithfull who was ‘naked under leather’ in Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), sparking adolescent fantasies among a generation of schoolboys that were a lot more interesting than the film itself. The Avengers, starting five years earlier, did the same with first Honor Blackman (Cathy Gale) and then Diana Rigg (Emma Peel). Blackman, a former World War II dispatch rider, had no problems with leathers, while Rigg ditched hers after one year in favor of the knit ‘EmmaPeeler’.

Interestingly, the original costume was rejected as too kinky. It made Steed’s second look like a female Diabolik in heels. There were also conical inserts to accommodate breasts which anticipate Madonna’s cone bra, designed by Jean Paul Gaultier for her 1990 Blonde Ambition tour, by a quarter of a century or so. Madonna has an updated version for her current MDNA tour while the original will be part of an exhibition about Gaultier at the Barbizon next year. The Avengers leather catsuit has been consigned to the dustbin of history.

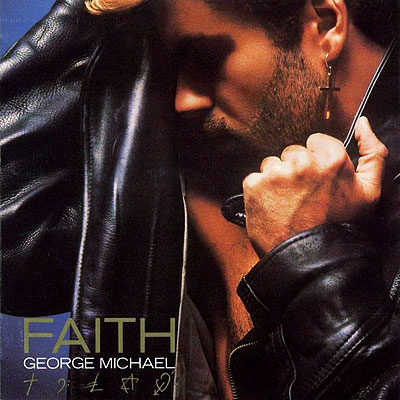

The elements of fetishism, the mix of sex and street cred, rebellion and rock and roll, were not lost on rock and roll musicians, whatever the sub-genre. The motorcycle jacket went from protection against the road and the weather to an image of action and attitude. Gene Vincent, George Michael, David Bowie, Elvis Presley, and Freddy Mercury, among others, to build or consolidate their fan base.

It took Punk to mix fascist and fetish chic, lacing it with anarchy and nihilism. The black leather jacket, worn, if not torn, sometimes studded, was paired with jeans, always torn, often black, and heavy boots, usually Doc Martens. The white ripped T-shirt – which Farren suggests owes more to Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire than to Richard Hell on the streets of New York (p.81) – was often a billboard for political or pornographic words or images selected to confront and offend. Tom of Finland and the Nazis found a common canvas.

“For Punks in the street, the style was motivated as much by poverty as by rebellion and was distinguished by all kinds of DIY customization: cutting, lettering and safety-pinning, often evoking the anger of Dada, the French Situationists and even early Conceptual art, while foreshadowing postmodern deconstruction,” Roberta Smith writes in the New York Times.

Needless to say, it was a Tom of Finland drawing of two near naked and aroused cowboys about to embrace that got Westwood and McLaren charged with an affront to public decency and not any of the purveyors of Nazi regalia.

Although leather clothing was shown by major designers by the 1920s, if not earlier – Jean Patou is but one example – Yves St Laurent was the first couturier to make it truly fashionable in the mid sixties. The black leather jackets of Punk were co-opted before Westwood and McLaren adopted it from New York’s Warholian scene.

But as Smith observes: “At once trashy and sexy, Punk provided excellent slumming opportunities… A Moschino full-skirted dress made of shopping bags is a delightful party gag, one that, fittingly, evokes Marie Antoinette in shepherdess drag”.

In terms of street wear, this became a casual, dressed-down, forever-young look. Now no couturier or pret-à-porter line would be complete without a black leather jacket.

Somehow that stack of twelve or so books grew to eighteen in the course of writing this piece. At this rate, I’m going to need a new place for all these books.

Farren’s Black Leather Jacket is the best overall book on the subject. It’s highly readable, well-illustrated, and, behind the breezy approach, better researched than usual. He wrote of his work in NME that “What the paper needed to complete the team was a gonzo alcoholic who knew the Bukowski-Thompson opening tactic of starting a story by describing the hangover”. It’s a fair description of the narrative style here as well, which quickly goes over the top and cheerfully stays there for the rest of its 96 pages. Describing Mad Max as “Cannibal Apaches on motorcycles” (p.88) is about as good a movie haiku review as it gets.

For him the black leather jacket – too often abbreviated as BLJ, which is not an obvious acronym, but is one letter shy of obscenity – is about protest and personal empowerment, its decorations about identity and idolatry. The term he uses to sum all that up is “magic”, which is what is was for him from when he was small.

He ends up complaining about fashion boutiques that sell “decidedly unmagical leathers”. Nevertheless he concludes, “Standard bikers wear the standard bike drag and the jackets get more worn, wrinkled and interesting right along with the faces of their owners…. On the gay strips the black leather jacket continues to hold its own…. The black leather jacket continues. At times it looks like it will go on forever” (p.96).

Recommended. If you want one book on the subject, this is probably the best choice.

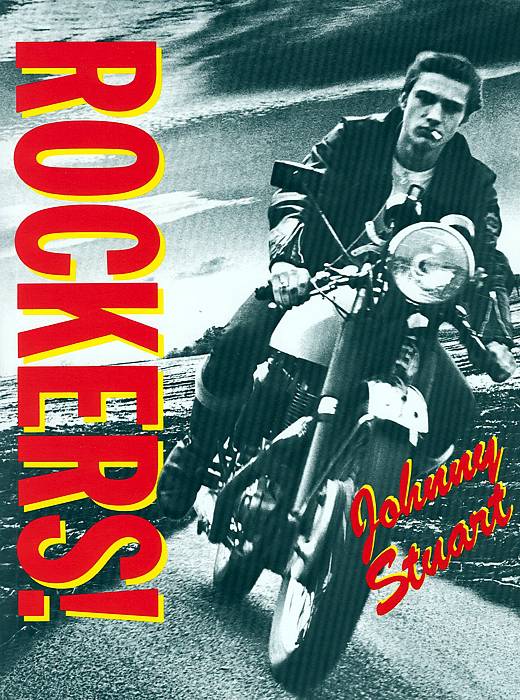

Stuart’s Rockers! (1987) covers the black leather jacket as part of its actual subject matter. The book was discussed in May as part of the Ace Cafe round-up. It is also a good choice for reading about the part the black leather jacket played in the lives of rockers, café racers, and other motorcyclists from the fifties to the seventies.

Stuart was something of an eminence grise (or perhaps noire) to Polhemus’s exhibition and catalogue Street Style, even to the point of lending pieces from his own collection to the show. The influence shows. Polhemus presents some 40 different ‘street styles’, from the forties to the nineties, from zoot suits to grunge and beyond. His main thesis is that ‘working class street style’ dresses up (teds or mods), while ‘middle class style’ dresses down (folkies or rockers). Some of the styles he includes seem marginal (zazous or rockabilly), while others seem to be omitted (yuppie or preppie [Sloane ranger]). To a degree, the style you see depends upon the street that you walk.

Because he does note all styles that favor the black leather jacket in one form or another, the book provides an insight into how prevalent it’s been and for how long. Eighteen of the styles he identifies use the black leather jacket as a sign/signifier of ‘membership’ in what he calls a styletribe. If I understand the requirements of each tribe, the jacket would not be unwelcome in close to half of the rest. The reader might well wonder why anyone would be surprised it became a fashion staple.

Ultimately, the book is more likely to be interesting to the fashionista than the motorcyclist. I’ll just note it as important in the literature.

Considering how often I quote or refer to Alford and Ferriss’s Motorcycle, it’s a bit of a surprise that I’ve never actually reviewed or discussed it. That gap will be addressed another time. As for the book itself, it is recommended as the ‘go-to’ volume for any discussion about any aspect of motorcycling and popular culture. By necessity the sections on a particular aspect of motorbikes and popular culture will be brief – fashion, for example, counts for approximately 13 pages out of the book’s total of 240 – but are quite informative.

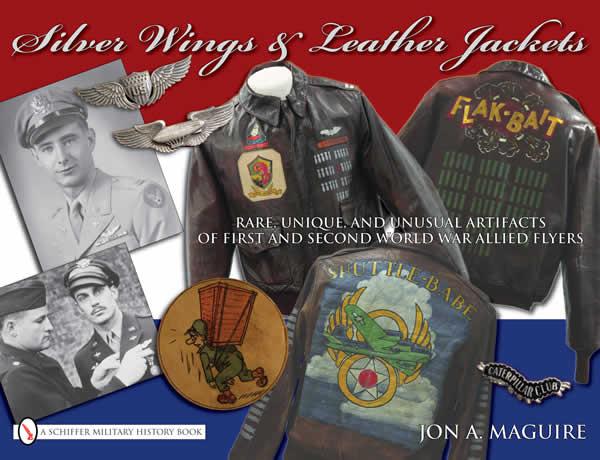

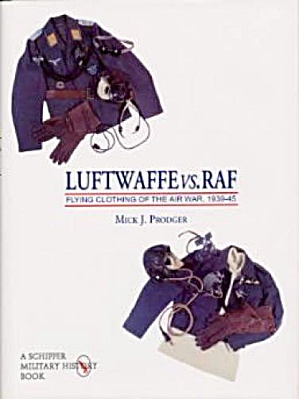

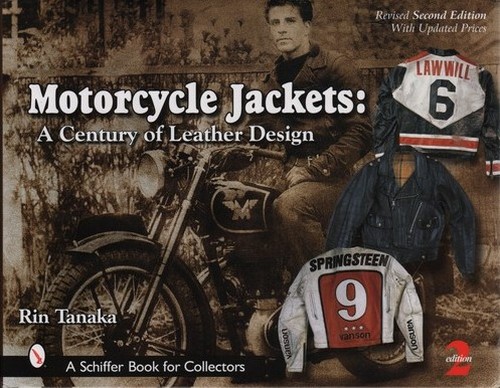

The next seven books take a different view of the leather jacket. Rin Tanaka’s Motorcycle Jackets: Ultimate Biker’s Fashions (2003) and Motorcycle Jackets: A Century of Leather Design (2006); Jon A. Maguire’s Silver Wings and Leather Jackets (2009); Maguire and John P. Conway’s Art of the Flight Jacket (1995) and American Flight Jackets, second edition (2000); as well as Mick J. Prodger’s Luftwaffe vs. RAF (1997) are all published by Schiffer, an imprint specializing in reference books for collectors, in this case flight and biker jackets.

The bulk of the books are pictures, with captions providing as full an identification as possible and, usually, values (prices) as well. Narrative sections are brief histories telling collectors what they need to know to be informed buyers. Each guide is prepared by some sort of expert in the field, either a dealer or a collector, and some are better than others. They are, in a way, coffee table books with solid research.

Some of the painted decorations on the flight jackets are fascinating, others beautiful (and not a few baffling), but too specialized for most. Maguire, Conway, and Prodger’s four books are fun and informative, although the target market is for collectors of World War II memorabilia in general and bomber jackets in particular. As the ancestor of how black leather motorcycle jackets are decorated, it’s not without historic interest. Recommended for completists and/or those with money to burn.

On the other hand, Tanaka’s two books, along with his history of Schott (2013), creators of the Perfecto, are a different matter. A biker born in Japan, the California-based Tanaka is fascinated by post-war fashion in general and motorcycle apparel and accessories in particular. He has produced a regular stream of books, some self-published, some published by Schiffer, including two devoted to vintage and contemporary motorcycle jackets. Those books include old boots, gloves, helmets, kidney belts, and riding breeches as well. There is also a separate volume dedicated to old helmets.

Tanaka started his research in 1994 when he realized that there were no books about old motorcycle jackets, or as we academic types would phrase it, when he realized there was a gap in the literature. His concept, at least in A Century of Leather Design, is to examine both the culture and the industry. Ultimately, the books are more about the products and the companies that manufactured them than the times in which they were produced.

Unfortunately, many of the companies were small and did not last for more than one generation. The records and histories are difficult to find, if not lost forever. Tanaka openly asks readers several times in both volumes to email him with additional information.

Leather Design is in its second edition. Ultimate Biker’s Fashions was produced between Leather Design’s first and second editions as a supplement and interim update. While each book stands on its own, Leather Design is more the field and price guide; Biker’s Fashions, more the history and anecdotes. Since the books are to a high degree interchangeable, they will be discussed together.

Both books round up the usual suspects to thank for help and contributions. Farren, Harris, Stuart, and, of course, the Ace Cafe’s Mark Wilsmore, for whom contributing to such projects as this constitutes an occupational hazard. Despite the iconic status of the Schott Perfecto, Leather Design is dedicated to Joseph Buegeleisen, whose company, Buco, manufactured the J-24, which Tanaka describes as “[t]he coolest motorcycle jacket of the century”.

Both books provide an overview of the history of styles and materials from zippers replacing buttons to steerhide replacing horsehide. Tanaka writes in Leather Design: “Motorcycle fashions have always set trends for each era. The D-Pocket jacket became the predominant style in late 1940s, but it was expelled from its popular position by Marlon Brando’s One-Star jacket after 1953” (p.37).

Citing such companies as Schott Brothers in New York and Leathertogs in Everett, Massachusetts, Tanaka suggests that “the American motorcycle jacket was born in the Northeast” (Leather Design, p.10). Given the overall history of the United States, that is probable without being conclusive.

He begins his history of the motorcycle jacket in the Edwardian age, which, while not inconsistent with the 1915 date, does suggest that the centennial of the black leather jacket may have passed unnoticed. Tanaka describes the first jackets as having a simple two-pocket style in front and plain back with no pleats. By the thirties the style has changed, becoming more like what we think of when we think of a motorcycle jacket. The front has a ‘W’ collar and a diagonal zipper, while the back has a center pleat and a ‘bi-swing’ design. By the fifties, the pleat has been abandoned in favor of a kidney panel with belt loops.

Tanaka presents the fifties as the Golden Age of motorcycle jackets. Certainly the brands have as much magic (in Farren’s sense) as the jackets themselves: Schott, Buco, Langlitz, Indian, and Harley-Davidson. Both motorcycle companies produced extensive – and now highly collectible – clothing and accessories for their customers.

He also notes the individual decoration of the jackets: “In motorcycle jackets ‘kustom’ means painting what you want to express, sewing patches on your jacket that proclaims your identity, and adding decorative studs with your own hands” (Biker’s Fashions, p.96).

The sixties brought the one or two-piece racing suit, with local racers supporting local manufacturers, who provided a more conventional custom or bespoke product. The leather racing jacket comes into its own, as do jackets in colors other than black or brown. Yellow was a popular color, and not just with Yamaha.

Tanaka’s favorite of this period may be ABC Leathers. “The most excellent leather designer, who rendered the greatest achievement in American racing history, is a woman named Clarice Amberg of ABC Leathers in South Gate, California” (Biker’s Fashions, p.186). His English frequently goes south but charm, accuracy and enthusiasm make up for a lot.

Amberg, who was also known for her lip-shaped logo, customized racing suits for the likes of American racing legend Kenny Roberts. However, her most notable achievement may have been for Easy Rider (1969). Peter Fonda told Tanaka, “My jacket was custom-made by a lady at ABC” (Biker’s Fashions, 186).

The books continue up to contemporary manufacturers and bespoke tailors. Vanson Leathers, Fall River, Massachusetts, gets a long write-up as does the older, more venerable Langlitz Leathers, Portland, Oregon. A legend in the Pacific Northwest, Langlitz is more toward the bespoke end, with limited general production and such special commissions as 45 flight jackets ordered by Neil Young to commemorate his 1986 Crazy Horse Tour with his staff and friends.

Other companies have an even more limited production and customer base. As Tanaka notes in Leather Design: “[L]ots of Hollywood celebrities discovered these craftsmen and ordered special jackets for movies, stage costumes, and their private motorcycle recreation” (p.265). Chrome Hearts, for example, counts Cher and Madonna, Iggy Pop and Eric Clapton among its clients.

The books are an excellent overview of the history of the motorcycle jacket in the United States, which may make them of limited interest for British readers. Yes, Lewis Leathers is mentioned. As is Mascot and Belstaff. And all favorably. But the products did not exactly penetrate the American market, to be kind about it. And in one of Tanaka’s rare errors, he identifies Ton-Up Boys as ex-Rockers. The chronological reversal aside, I didn’t know there was such a thing as an ex-Rocker.

Recommended for those who want a history of the black leather jacket that specifically deals with the motorcycling life. Caveat for those who want to collect jackets. Prices are already out of date by the time a guide rolls off the press and the emphasis here is on American product lines.

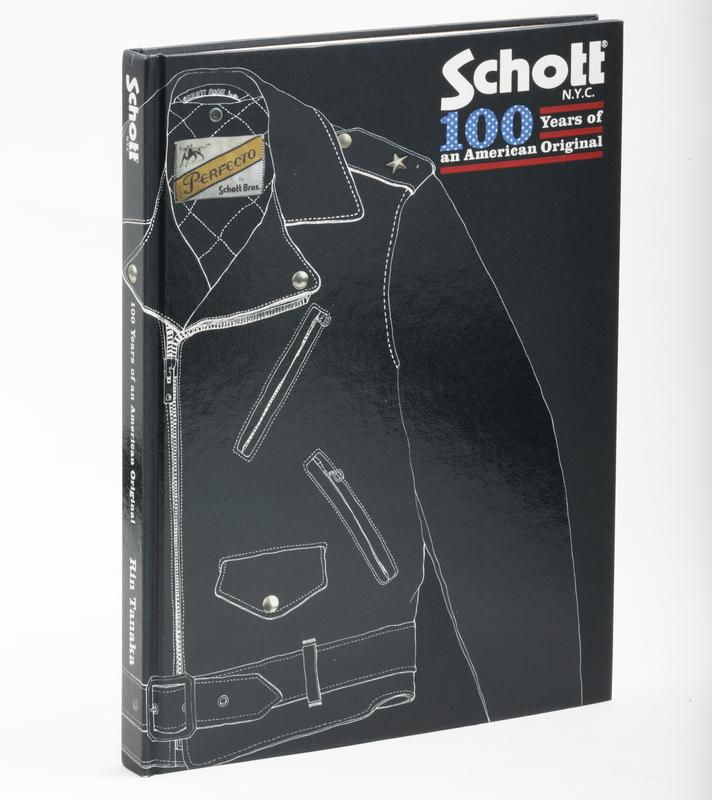

Tanaka’s Schott: 100 Years of an American Original is a company history celebrating its centennial. Given Schott’s claim that it invented the motorcycle jacket and Tanaka position as ‘the’ expert in motorcycle jackets, it’s a match made in public relations heaven.

The book celebrates all things Schott. It’s not a book to learn about Schott’s rivals or reversals, but to look at vintage photographs, giggle at how dated old advertising is, and smile at amusing anecdotes.

The company – identified alternately as Schott Brothers or Schott N.Y.C. – was founded in New York’s Lower East Side in 1913. Within a couple of years its factory had been moved to Staten Island, and a few years later to New Jersey, where it remains to this day. Most born Manhattanites regard Staten Island as part of New Jersey, but for an accident of American politics, making “Schott N.Y.C.” questionable at best. Regardless, Schott is the only reason anyone would have to visit Perth Amboy.

Schott of course doesn’t just claim credit for the Perfecto, but inventing the motorcycle jacket itself in 1928 at the request of a Harley-Davidson dealership on Long Island. Irving named it the Perfecto after his favorite Cuban cigar. Close to a quarter of a century later, someone working on the costumes for The Wild Ones purchased a One-Star from Schott’s shop in Los Angeles. The rest is history, which is covered in a double-page spread. And, yes, this would mean that while the black leather jacket is about 100 years old, the black leather motorcycle jacket is close behind it at 85.

Of course, Dean and Brando weren’t the only celebrities to wear what to many is THE black leather motorcycle jacket. Tanaka happily lists such bold names as Slash, Lou Reed, Lady Gaga, Johnny Rotten, and Bruce Springsteen. Such bands as The Ramones and The Beastie Boys even made the jacket part of their stage presence.

The company history itself includes the family tree, from Irving (who founded Schott with his brother, Jack) to his descendants – the great-grandchildren Jason, Oren and David – who are still involved with the firm. Every label ever used gets a nice photo spread and even non-motorcycle product lines through the years are covered. Such special collections as James Dean or Kenny Rogers get sections of their own.

Because the book presents pictures and pictures of Schott products and advertising along with family and old corporate shots, it’s essentially a coffee table item with an ‘official tale’ of the company’s success. To be fair, a successful business that has been in the family for a century is something to be proud of, at least in this day and age in North America. Most have closed or been bought out. I’m a little surprised that the local media here hasn’t made more of the anniversary.

Nevertheless, the book itself appeals mostly to those for whom Schott has special significance, probably a collector of motorcycle jackets in general and Schott in particular.

The rest of the books are problematic to a greater or lesser extent. The Leather Book covers not just the black leather jacket, but also anything ever made of leather: bags, shoes, luggage, upholstery, saddles… It covers how leather is made from skin as well as the different kinds of skin used to make leather. Ultimately it focuses on industry statistics, with the emphasis on luxury goods – Hermes, J.P. Tod’s – though Schott and Doc Martens are covered as well.

Unlike the luxury goods it admires and promotes, the book itself is shoddily produced. Careless translation is compounded by careless printing. Page 186 in the edition I read was still in French, untranslated into English. Page 148 credits Edith Piaf with the lyrics to a song Quilleriet claims is called The Man on the Bike. The song was written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller and is called Black Denim Trousers. The French translation, which Piaf recorded, is called L’homme à la moto.

Worse, instead of going back to the original English lyrics, the translators, Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods, translate the French translation into English. “He wore black denim trousers and motorcycle boots, And a black leather jacket with an eagle on the back, He had a hopped-up ‘cycle’ that took off like a gun, That fool was the terror of Highway 101” becomes “He wore biker pants and boots, and a black leather jacket with an eagle on the back. His bike, which took off like a cannonball, sowed terror throughout the region”. Crediting Piaf for Leiber and Stoller’s song is common among European researchers, and no less irritating for all that. The translation however violates the Geneva convention. Not recommended.

The Leatherman’s Handbook does have interesting information about the image and the history of motorcycles and gay bikers in certain times and places. Townsend, an industrial psychologist, has taken care with his research. It is however incidental to the main point of the book, which is how to become a sado-masochist. Recommended for those who like to have spanners tossed into their works.

Leather Jackets, part of a series called Hamlyn 20th Century Style, would be called a coffee-table book if its size weren’t more appropriate for a cigarette table. Essentially a nice but predictable selection of photos, and virtually no text beyond the brief captions. I’m not sure good editing would have saved this book from being marginal, but a caption asking whether Jim Morrison of The Doors can be taken seriously in his leather pants is accompanied by a photo of Morrison from the waist up (39) doesn’t help matters. Not recommended.

Punk: Chaos to Couture is the exhibition catalogue to the Costume Institute’s show at the Metropolitan Museum. It has a bad introduction by Andrew Bolton; a good essay by Richard Hell; a disingenuous one by John Lydon; and solid piece by Jon Savage that’s well-worth reading. The exhibition itself began with a recreation of the unisex restroom at CBGB’s before going on to how Punk was co-opted by haute couture, essentially going from the pissoir to the piss elegant. Sadly, Savage’s essay doesn’t save the catalogue from being a waste of money. Not recommended.

Or Glory: 21st Century Rockers is the edited, paperback version of Pride and Glory: The Art of the Rockers’ Jacket. Essentially a photo-essay of, well, the studded, patched, and painted jackets worn by Rockers new and old, male and female, some with their bike, some without. Friedrichs attempts to make his Rocker subjects raw and real, and for the most part succeeds. Other shots are a little too studied, too posed the camera, too ready for the close-up. The paperback is a better deal aesthetically and financially. The shorter cheaper format forced Friedrichs to edit, making for a visually tighter series of photographs at about a third of the price. Recommended for the Rockers and the Rocker wannabes.

Meanwhile, my leather jacket has come back from the tailor, pocket repaired, ready for more years of abuse, until the jacket has more character than I do.

Jonathan Boorstein

jonathanb@theridersdigest.co.uk