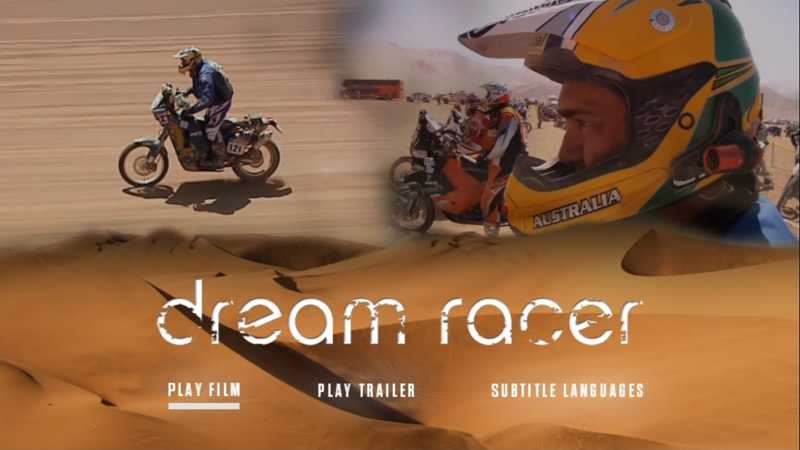

It seems incongruous to review a DVD that’s been on general release since 2012. However, Dream Racer has recently been nominated for another slew of documentary awards to add to the considerable amount of recognition it has gained since its release, and together with the fact that its background subject – the Dakar Rally – has, at the time of this review, just completed its 2016 iteration, that’s all the excuse the Digest needs to take a look at what is one of the great bike films.

Dakar Fever

Dream Racer is about then-39-year-old former motocrosser Christophe Barriere-Varju’s attempt on the 2010 Dakar Rally, and producer/director Simon Lee’s parallel ordeal in documenting it. There is the overall theme of ‘live your dream’ etc. that concerned me at first because it is a theme that has been done to death in motorcycle culture and is something that this reviewer has recently become immunised from with respect to all that ‘biker spirituality‘ schtick and its use in marketing; but thankfully, Lee doesn’t bludgeon the viewer over the head with it, preferring to tell the story by letting it tell itself – letting the actions do the talking, if you will. Walking the walk vs. talking the talk.

A bit of background is in order on the protagonists and the event itself:

French-born Christophe Barriere-Varju spent his formative years in West Africa’s Ivory Coast, and got into motocross at the age of 14, where he rapidly came to dominate and become one of the region‘s star riders (below). For reasons that are not elaborated upon in the film, he retired from MX, went to the United States to complete his education and eventually, in his late-twenties, moved to Australia where he now runs his own business consultancy.

It seems that during this period of adult responsibility, the racing bug never left him (some bloke once said ‘racing is living, the rest is just waiting’) and some time around the mid-2000s, Barriere started cultivating a desire to get off-road again and to take on the Dakar Rally. It’s interesting to note that the film acknowledges one previous attempt by Barriere on the Dakar the previous year (in 2009) which ended in injury and retirement, but doesn’t mention his two entries in the ’proper’ Africa-based Dakar a few years earlier. This omission makes the viewer think that Barriere is less experienced on the event than he really is. I assume it is to do with the licensing requirements that would be involved in showing old footage of the event and its impact on the film‘s budget. That is not a criticism. All that info is available on the internet [1].

I think the omission is a shame though, because Barriere’s interest in and obsession with the Dakar Rally is clear when he says: “I love the desert – you feel like a small ant in the immensity of the landscape”. In this respect, Barriere is basically a disciple of the gospel of the late Thierry Sabine, the founding father of the original Paris-Dakar Rally with its epic traverses across the Sahara Desert that first ran in 1979. Sabine was well-known for romanticising the desert and for aiming the original concept of his event squarely at amateur adventurers whom he fully expected to get lost out there in the Sahara and consequently share his vision. During one of the rally’s early editions, Sabine was asked who he believed would win. His response summed him up: “the desert” [2]. I highly recommend hitting YouTube for a few hours and searching for clips of the rally during the years 1979-1989, because you won’t believe it (remember Mark Thatcher getting lost in 1982 and how the entire Algerian army was mobilised to find him?).

Aficionados of the Dakar claim the original ethos and philosophy of the rally died along with Thierry Sabine when he was involved in a fatal helicopter accident during the 1986 event. In subsequent years, the ‘works teams’ started to notice the rally and the media coverage it attracted in France, bringing vast budgets, purpose-built hardware and military levels of logistics to the rally, so it stopped being an amateur’s event.

The rally’s presence in the countries of West Africa also became untenable over time, as it was never able to separate itself from the changing politics of the region. A number of incidents involving armed attacks on competitors (and constant threats thereof) by militant groups eventually forced the rally to abandon the region altogether after 2008 in favour of South America and the terrain around the borders of Argentina and Chile, and latterly Peru and Bolivia. If you’re wondering why the rally retains the name of a West African city, it’s because if the event wasn’t called the Dakar, then it wouldn’t be the Dakar. In the 21st Century, the continuity of the brand is everything.

Barriere’s motivation as an amateur entrant then, is intrinsic: he’s competing on this rally against himself and correcting the injustice of having to retire the previous year (“I have to finish this race”). He’s also competing against Western definitions of fulfilment and success. Despite confessing no affinity with the Buddhist statues that surround his house, he lives like an ascetic by having virtually no furniture – one of the consequences of orienting his entire life around the prospect of the Dakar. In fact his house is just a temporary base, selected because of its proximity to sand dunes for training on. Barriere’s ‘home’ is on the Dakar Rally itself, on the special stage, with no outside distractions.

Barriere allows nothing to deflect him from training and preparing for his goal. The film starts some six months before the 2010 rally, where producer/director Simon Lee first becomes aware of Barriere’s intentions. The two team up to make the film because at their core they are motivated by the same thing: the desire to tick certain boxes and to prevent a life of Groundhog Days. When the decision is made, Barriere is up against the Sisyphean task facing the lone amateur entrant of raising the massive budget required to do the rally, along with procuring a bike to ride and its associated mass of spare parts (not to mention the cost of getting it all shipped to Argentina), all while training his body for the upcoming ordeal.

Lee is faced with the job of obtaining backing for the film’s production – a niche, non-mainstream film if ever there was one. Where the two differ though, is that Barriere continues to use his business consultancy in the attempt to procure finance and sponsorship and does so with the total single-mindedness described above and free of external influence; whereas shortly after the birth of his second child, Lee goes ‘all-in’ by quitting his advertising job to devote himself full-time to the cause, bringing his family along for the ride whether they like it or not. Does a man really have the right to do something like that when he has responsibilities beyond himself? The question is one of the central tenets of the film, and you can imagine how well Lee’s decision went down with his family.

In the course of these separate approaches to the same goal, the two almost fall out a number of times and commendably the film does not shy away from showing these disagreements; and it is a change to see exactly how much hard graft and self-belief it takes to do something like this and how much conflict it generates from non-believers, when so much moto-adventure is depicted to happen spontaneously and within an economic vacuum.

“Can You Ride Without Triceps?”

Barriere eventually benefits from what those Buddhas around his house would call some ‘good karma‘ and suddenly it’s on, the budget is in place, he’s checking-in ten sets of tyres and all his spares as excess baggage at the airport and he’s on his way to Buenos Aires for the start of the Dakar Rally.

The film gets into its stride when the rally begins, but there’s an interesting sequence before the start of the rally where it becomes clear how massive an undertaking the Dakar Rally now is, as Barriere has to go through full days of form-filling, scrutineering, and even a class on how to use the organiser-supplied GPS and the event’s road book (that covers a 10,000-km route).

Barriere will have been by no means the rally’s only ‘one-man team’, but it’s an indicator of how the event has distanced itself from Thierry Sabine’s original amateur ideals and become a massive corporate machine. Does the rally’s presence in Chile and Argentina benefit those countries and their populations? The massive crowds of spectators that line the route certainly indicate a far greater level of public interest in the rally in South America than it ever had in Africa, partly because of the obvious consideration of population density.

Commendably though, the film does not make any attempt to politicise the rally or assess its place in the world (so neither will I) and is content to depict a population that is clearly passionate about it. The start in Buenos Aires is a national holiday because the rally always traditionally begins on New Year’s Day, so the entire city seems to turn out for it. On the special stages, spectators jump on crashed cars and return them to the road in seconds. In even the most remote parts of the route, people emerge from nowhere bearing Coke bottles full of petrol to give to stranded riders. More evidence of the level of interest in the rally is seen when Lee and freelance journo Jacob Black (who joins the crew at the start and is there to do Barriere’s PR) rent ’the last hire car in Buenos Aires’, cover it in sponsors’ logos in order to conform to the requirements for a press car, and are subsequently and frequently mistaken for competitors as they are mobbed everywhere they stop for petrol.

The film is rightly focused on Barriere’s rally and as it progresses he is shown as a man in his element. Lee and Black on the other hand are constantly wracked with self-doubt, with Lee in particular getting regular reality checks from back home on Skype. We see their often comical attempts to keep up with the rally in their indefatigable hire car that was never meant to do 10,000 km in 16 days (P.J. O‘Rourke once said that the fastest car in the world is a hire car). Just as Barriere deals with fatigue, injury, sleep deprivation and the demands of being a one-man team in a rally that would be more civilised if the day was 29 hours long, Lee and Black are reduced to kipping in fields and parking outside houses so they can jack into unsecured WiFi in order to file reports and do Skype. They go on to risk hypoxia at 4,000 metres altitude in the Andes where Barriere briefly appears beside them on a road section like an oxygen-deprived hallucination. Their rally is as much of an adventure as Barriere’s and they aren’t even on a bike.

Barriere’s bike starts breaking under the relentless pace and so does Barriere’s body when horrendous spills are captured by helmet cam, so naturally he invokes the racer’s prerogative to ignore injury of any kind, even when there is no official result at stake because he’s actually down in the bottom half of the leaderboard – at this level the leaderboard is irrelevant and the only competitor is himself [sidebar: Hubert Auriol was the grand master of the pain threshold in 1987 when he continued to ride with both ankles broken. The footage of him arriving at the end of the stage this happened on his horrific. It is available on YouTube…].

If you’re still in any doubt as to Barriere’s motivation behind this self-inflicted ordeal, there is one priceless scene about two-thirds in where his joyous reaction to one particular section of a stage – the same one he retired on the previous year – tells you everything you need to know about this film and its message, and if you still don’t get it or even disapprove, especially at the rally’s end, then you have a heart of stone.

Dream Racer is an excellent film. Like all great bike films, it isn’t about bikes at all and is instead about the people who ride them. It is far better than On Any Sunday, which many still consider to be a ‘set text‘ and a recruitment film for bikers despite it being ancient. Dream Racer is better than TT: Closer To The Edge too because it doesn‘t seek to deify the event it features (although both films deal in the ‘live your dream‘ theme). It is not clear whether director Simon Lee is a biker himself, and if he isn’t then the film is all the better for it as it doesn’t get bogged-down in tech-talk. Dream Racer’s message is such that the film should be shown in schools as an example of the power of self-belief and as an antidote to an education system that encourages conformism and complacency.

The film also gives considerable coverage to a rally that has a rich, eventful and controversial history that is worth spending some time exploring. As to all the arguments about the modern Dakar Rally’s professionalism and commercialism versus its roots in amateur adventuring, in Christophe Barriere-Varju and all the other self-financing one-man/woman teams that have entered it over the years, the classic amateur’s Dakar still exists.

Thierry Sabine would have approved of this film.

Stuart Jewkes

Further reading:

A downloadable PDF from the official Dakar homepage that details the rally’s history from 1979-2009.

References:

[1] Interview with Christophe Barriere-Varju on MotorcycleUSA.com (14/5/15).

[2] Quote from the BBC4 documentary ‘Madness In The Desert – The Paris-Dakar Rally’.