In case you’re wondering, ‘fescue’ is a type of grass, widely used throughout the UK for creating sports turf.

Which is sort of appropriate for this feature. For most of my working life I’ve been involved in maintaining grass, spiking it, rolling it, marking it, harrowing it and sowing it.

And then scarifying it, slitting it, fertilising it, watering it and using many different kinds of machines to mow it, mostly towards the further enjoyment of bowlers, strikers, batsmen, prop forwards and other people who enjoy playing with their balls.

But I’ve never been involved in actively encouraging people to ride motorcycles competitively on grass.

That’s a different kettle of fish, and seems to involve using equipment called ‘sheep’ to regulate the length of the sward while also taking care of irrigation and fertilising.

Then you stick in several hundred wooden stakes linked together with a few miles of rope roughly in an oval shape, mark a white inner line similar to a cricket boundary, invite several competitors along, and then you’ve got the makings of a grasstrack meeting.

If only it was that simple.

As a sport, grasstrack racing began in the UK way back in the 1920s, with a crowd of more than 20,000 watching one of the first organised meetings at the Cambridgeshire Show as 16 riders took to the horse trotting track for 6 laps.

I’ve described the ‘roots’ (see what I did there?) of grasstrack before in The Rider’s Digest, this is from ‘Making Tracks’ in issue 176 (which is available in the on line archive):

“Around this time (between the wars) the members of The Sidcup & District Motorcycle Club, which had been founded in 1928, primarily as a trials and grasstrack racing organisation, were looking for a new base for their off road events, having lost the use of their previous track a few miles away in a valley near West Kingsdown.

“Legend has it that a relative of one of the club members, Wally Lock was working as a delivery boy in the area, and told the club committee that he’d found a piece of land that might be suitable for grasstrack racing. This turned out to be the case, and with permission from the owners, Brands Farm continued to be a grasstrack circuit until the late 40s.

Early grasstrack differed from what we know today, which has many similarities to speedway, with the bikes back wheels sliding out on the left hand bends. In those far off days the tracks featured left as well as right-handers, with the average speed on the kidney shaped grasstrack exceeding 60 mph.

“Centre and national meetings were held, establishing Brands Hatch as a well known circuit among the grasstrack fraternity, but then a cinder track was laid, forcing the grasstrackers to find a new circuit. The land was later sold off, the cinder track was replaced with Tarmac and Brands Hatch Stadium was created.

“Moving their events to Canada Heights in 1948, the club initially held scrambles meetings there while members formed working parties to grub up the remains of the apple orchard, with an inaugural grasstrack meeting held in the 1950s on the flatter land at the top of the hill, ironically known as ‘the orchard’.

Following that meeting it was decided that the site wasn’t particularly suited to grasstrack racing and the club focussed on scrambling, a term derived from the early origins of trials riding, where after timed sections balancing over logs and boulders the riders were relieved to have a ‘mad scramble’ to the close of the stage.”

At first glance it’s blindingly obvious that grasstrack is related to speedway, the corner sliding styles are similar, the race length is the same, although the track length for grasstrack is often more than double that of speedway and grasstrack races usually have more riders, so it’s likely that at some point in the distant past it was decided by someone somewhere that they would become distinctly different sports.

I also talked about the beginnings of speedway in another issue of the Digest, 179, where I gave a breakdown of the principals of the sport, but I believe that another chunk of ‘cut & paste’ would be a bit of a cop out, so I’ll leave it to you to go back through the archive and seek it out.

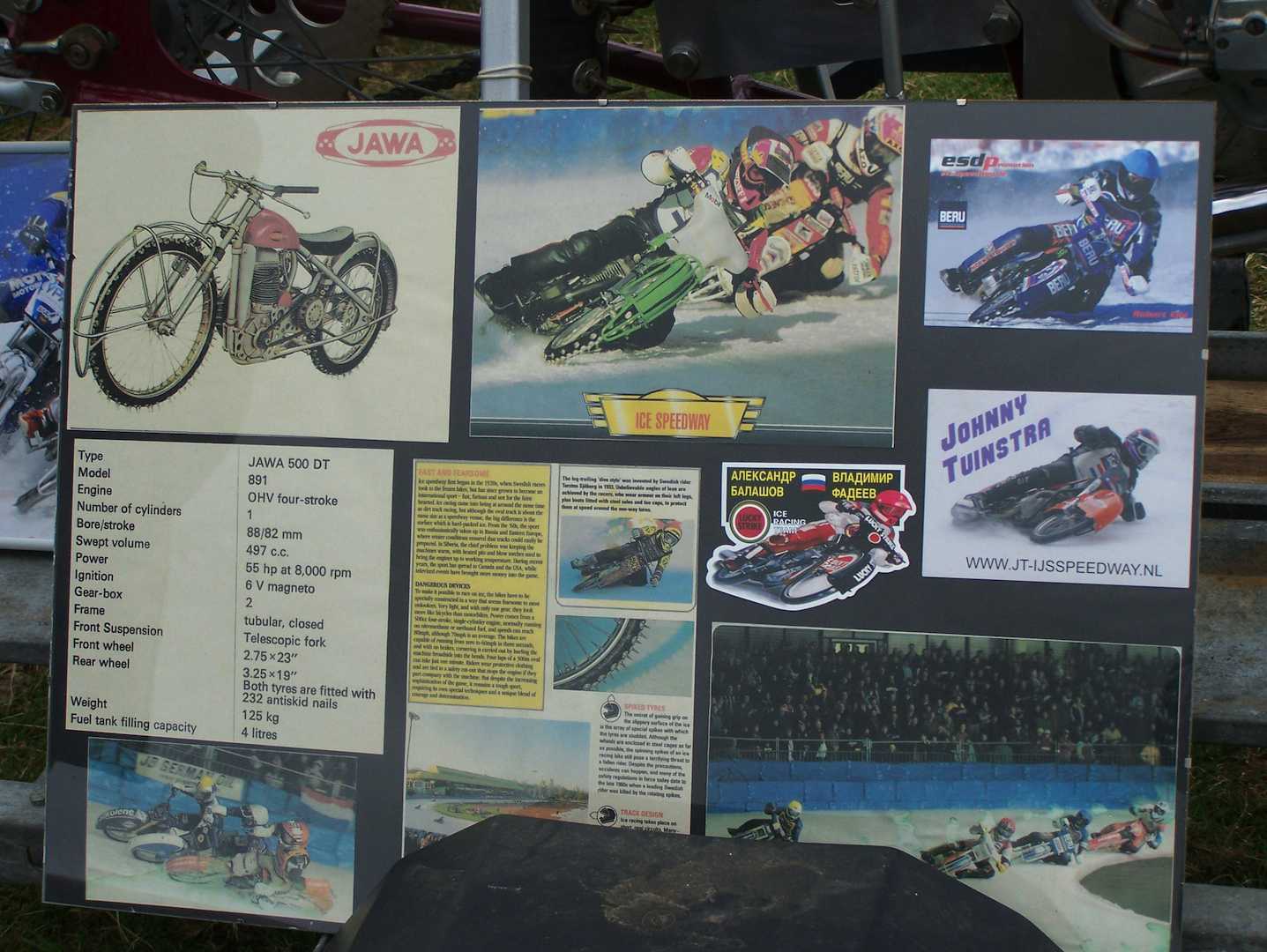

There are other similarities too, the riders wear the same gear, the steel shoe is worn on the left boot for solo riders, the engines are predominantly made by Jawa and GM, and from a distance the bikes do look similar.

In fact, solo grasstrack bikes are up to a foot longer, have two gears, usually changed by a second lever offset to the clutch lever, and as well as similar front suspension to speedway bikes, they also have rear suspension, most commonly a single shock setup similar to what you would find on many street legal machines.

Suffice to say, despite the obvious differences, there remain definite links and comparisons between speedway and grasstrack. Back in the 1970s I used to get along to a few of the meetings that were dotted around Kent with my neighbour, who competed for a few years before moving on to speedway.

In those days (if my memory serves me correctly) grasstrack was very much in the shadow of speedway, with household names such as Ivan Mauger, Peter Collins, Ole Olsen and Barry Briggs featuring on the TV as well as the back pages of the tabloids. It seemed to me at the time that most people had never heard of grasstrack racing, with the inevitable ‘it’s a bit like speedway, but on a grass track’ being often repeated to the uninitiated.

From lifelong speedway fan Martin Teraud’s account in issue 179 of the current state of the sport, crowd numbers are dwindling, despite coverage from Sky Sports, and I can’t help wondering whether the traditional weekday evening fixtures and strict noise curfews at the venues are having an impact on the popularity of speedway.

Not everyone can manage to get home from work and then get to an evening meeting every week, and paying around fifteen quid for 15 minutes of racing maybe doesn’t stack up financially.

I was therefore pleasantly surprised to see the number of people that turned up to watch the recent FIM Long Track World Championship at Swingfield, near Dover. The fact that it was held on a Sunday afternoon may well have helped, but on crowd numbers alone I would dare to suggest that grasstrack has now become more popular than speedway in the UK. A bit of a ‘John Lennon’ statement if ever there was one, but I’d be happy to be proved wrong.

The posters advertising the event state that grasstrack is the world’s fastest off road track sport, the track in question is a large oval, usually on a farm somewhere, complete with the undulations you would expect to find in a sheep field.

Having looked at solo grasstrack bikes in some detail and decided that apart from the rear suspension and gearboxes they bear more than a passing resemblance to their speedway cousins, the sidecar outfits are a different proposition altogether.

The single cylinder roar of the Jawa engines is replaced by the howl of the Japanese four cylinder engines usually associated with race replicas such as Fireblades and R1s.

I spoke to Will Offen in the sidecar paddock at Swingfield, who along with Nicky Owen rides a tiger striped machine constructed by grasstrack legend, the late Mick Steer. Will told me that his machine (number 80) was fitted with a 1,000cc Yamaha Exup engine, and was probably the oldest at the meeting.

The riders of these formidable machines lean forward across the airbox directly above the engine, while the passenger will be throwing themselves around in any one of a number of positions on a tiny platform hanging on by hand or foot to a substantial grab rail, with the ‘sidecar’ wheel seemingly leaning in at anything up to 45 degrees depending on the riders’ preference. There was also an option to move the third wheel forward or backward on the frame depending on the track and conditions.

Will explained that he and Nicky would choose sprockets to suit an individual circuit; Swingfield’s track is 600 metres long, and considered ‘fast’. There is also an option to lengthen or shorten the wheelbase by adding or removing links from final drive chain and using the elongated slots in the swing arm, the spindle ends doubling up as the rider’s footrests. ‘A shorter wheelbase will give you more traction’ added Will.

With regard to choosing suitable gears for a track, Will said that he had kept the full set of gears in the Yamaha, and for Swingfield would be using 2nd and 3rd, changed by a second lever on the left handlebar, which was linked by a large red cable to the gear selector.

This machine is a work of art, the beautiful hand brazed framework had been sculpted around the riders by Mick Steer, from the leading link Earles type forks through to the infinitely adjustable third wheel.

Having a nose around the paddock I couldn’t help noticing that in contrast to the 1200 stakes and miles of ropes making up most of the fences around the circuit, the paddock was divided in two by a sturdy looking Heras fence – the type you see on building sites to keep the Herberts out, with solos on one side, and sidecars on the other.

I asked a guy selling ‘Rhino Goo’ bike cleaner if there was any particular reason for the strongarm fencing between the two factions. He seemed as baffled as I was, but suggested that as the FIM were overseeing the World Championship aspects of the meeting the necessity for the fence was likely to be one of the requirements of their expansive rulebook.

Wandering through the solo paddock, it was interesting to see and hear the riders and crews from France, the Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and Australia prepping their bikes alongside Team GB.

From the crew vehicles registrations it was clear that most of the teams had travelled overland to the circuit, with one obvious exception, the Australians.

I asked one of their team about the logistics of getting the riders and the bikes over to Blighty to compete against the Europeans. He told me that the Aussie riders were mostly professionals who had bikes and equipment in several different countries, and would fly to wherever they were needed with key crew members in time to set the machines up for the races.

Things have evolved and moved on in international grasstrack (known as ‘Longtrack’) circles, but on the domestic scene it was somehow reassuring that some things hadn’t changed that much from when I last attended a grasstrack meeting some 40 years earlier. Among the ‘names’ on everybody’s lips in those days were Alf Hagon, Don Godden and Graham Hurry.

Those names still very much in evidence, we’re all aware of the Hagon family and their suspension products in mainstream biking, and the late frame builder Don Godden’s family had donated the magnificent ‘Don Godden Trophy’ which had been unveiled at the meeting to be presented to the winning nation, and Don’s son Mitch is team manager of the GB squad.

The organisation behind this impressive meeting had been headed by the Chairman of Astra Grasstrack Club, the aforementioned Graham Hurry, former national solo grass track champion and father of clerk of the course Paul Hurry.

I asked the commentator where I could find Graham, he told me that he was always on a mission, and was usually walking up and down carrying a hammer. When I eventually caught up with him he was sitting on his roller.

Not a luxury limo as you might expect, but a large vibrating roller attached to the back of his tractor. Graham told me that he usually starts planning the meeting in January, with a steady flow of organisational duties throughout the year, and the workload really ramping up for the three weeks immediately before the event.

In addition to insurance, permits, FIM and ACU paperwork, Graham also has to organise coverage from the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade for both the competitors and the general public, the track maintenance crew, the start line girls, the point scorers, the commentators, the staff working on the entrance gate, the car park attendants and the marshals.

There is also the small matter of liaising with the local council, the landowners, event sponsors, advance publicity, the caterers, marquee companies and not forgetting the all-important toilets.

Then there’s a very professional glossy A5 brochure, the p.a. system, and the starting and safety lights. I could go on, but I’m sure you get the drift.

Having been involved in outside events in the past, I know that to organise something this big takes a great deal of time, creating a lot of stress and sometimes causing sleepless nights worrying about the weather conditions. People might think that to organise an outdoor event like this in August would be relatively straightforward, but less than a week later many parts of Kent were flooded following torrential rain.

While chatting Graham suddenly broke off and striding purposefully towards the track started directing the driver of a JCB who was levelling the track, scraping up buckets full of soil and then spreading them in depressions.

Once the levelling work had been completed, a chain harrow was dragged around the track. It was then rolled, followed by a water bowser sprinkling hundreds of gallons of water around the track.

And then he was back, talking about the length of the track, (600 metres) the cost of staging this meeting (£35,000) and the substantial prize money for the winning team, which is all well and good, but with unpredictable weather conditions in the weeks leading up to the meeting the Astra Grasstrack Club could well have been facing huge losses.

In the event, the weather was fine and dry, with a fairly persistent wind blowing in from the southwest, and four and a half thousand spectators arrived in a steady stream to enjoy the event. There were no restricted areas (obviously apart from on the track) with the crowds free to wander around the paddock, the atmosphere was relaxed, the bar was doing great trade and it was good to see fans of all ages enjoying the sport.

Graham has said elsewhere how nice it would be to have a purpose built stadium, with covered in pits, floodlights, and the ability to run the meeting in the evening, but the reality is that it is extremely difficult to try to create a super stadium in a farmer’s field in just a week.

For the record, I had a great time. The facilities were excellent, the racing was unbelievably fast, colourful and exhilarating, and while there appeared to be very different levels of ability between some of the solo riders, the sidecar races, travelling in the opposite direction around the track were absolutely spectacular.

Since it’s inception in 2007 the German team has won every one of the FIM Team Longtrack World Championships, so there was considerable pressure on their rivals before a wheel had even turned. With the new Don Godden Trophy for the winning nation to take home, no team was more aware of the need to win than the Brits.

In the event it was the French team who were looking good to take the title throughout the heats, but by the end of the afternoon they had only managed to clinch the runner up spot, just two points behind the victorious Dutch squad, with Team GB taking the third step on the podium, ahead of the Germans, the Australians, the Finns and the Czechs.

The trophies, including the Mick Steer Sidecar Racing Trophy, and the aforementioned and quite stunning Don Godden Trophy, were awarded by Don’s wife, Chris Holder – the current World Speedway Champion – and speedway legend Barry Briggs.

It seemed to me that the only person who wasn’t watching the racing was Graham Hurry, who spent the whole day scrutinizing the track conditions, walking about and trying to ensure that any depressions or ruts were quickly filled and levelled between the heats, getting the dust damped down as much as possible and the track rolled, trying to keep the FIM officials and the crowds happy, a fine balancing act.

And for that, he deserves a medal.

Martin Haskell

With thanks to Graham Hurry and the Astra Grasstrack Club

For further fixtures in the grasstrack calendar, visit www.grasstrack.net