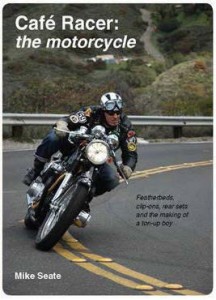

The world of the contemporary café racer in the United States is more properly addressed in Seate’s Café Racer: the Motorcycle (2008). For the past five or so years Seate has made a cottage industry out of it, not only with the publication of this book, but also a bimonthly magazine, Café Racer; a documentary, Café Society (2010); and a TV series, Café Racer, which is still playing on Discovery’s Velocity Channel here in the States. A frequent guest is singer/songwriter Billy Joel, who has his own motorcycle shop on Long Island in New York. His motorcycle accident is almost as famous as Bob Dylan’s.

But the book isn’t about The Piano Man; it’s about nostalgie de la boue, that yearning for authenticity through retro/revival. That may – or may not – explain why the introduction by Dave Degens doesn’t mention the book, the author, or the conceit. It’s a short, generic personal essay redeemed by a good definition of the original café racers: “a bike you could use to go to work on all week and win a race on at the weekend” (p.7).

As for the book itself, it’s a brisk and breezy 160 pages, filled with mostly color photographs taken by Seate, and includes such historical or anecdotal sidebars as “Paul Dunstall’s Top Ten Tips for Café Racers” or “The Terrible Tiddlers: Small Displacement Café Racers”, the two that I liked best. The narrative itself is a hotchpotch of profiles of people involved with the contemporary café racer scene, Seate’s own tale of how he became a “café racer”, as well as oral histories and summaries of the history and traditions of café racers.

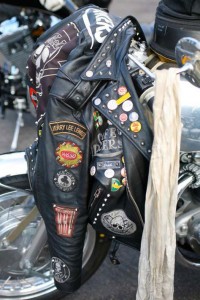

A typical profile might be RikkiRocket, a rock musician (as opposed to rocker) who started a national “patch club” called Brit Iron Rebels dedicated to building and racing café racers. Seate quotes a club officer as saying, “The club is based on the retro style of the rockers of the fifties and sixties in Great Britain and our membership encompasses all classic and retro British motorcycle enthusiasts: the collector, the purist, the racer, and radical customizer” (p.67).

Rockett goes a bit further into nostalgie de la boue territory. Membership is made up of “older folks looking to capture that snapshot of our carefree days and younger members seeking an identity that is much more unique than the countless ‘me-too’ biker clubs”. Needless to say, the California-based Rockett has helped produce a documentary about the Rebels: Brittown

Seate also traces his own history and interest in café racers from an early encounter in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to owning a Triton, which he was ill-prepared to maintain. Years later he learned that most café racers were maintained by bodging.

Intertwined with those two threads is a potted history of café racers in general and the Ace in particular. Most of the history is about what one would expect with a few interesting exceptions and observations. Seate overtly connects the racer/rocker’s “flyboy” look to the jet age and his attitude to the then presumed threat of complete nuclear destruction, making the café racer much more a specific 1950s cultural phenomena. He also notes that the British followed (and still follow) motorcycle racing much more closely than Americans.

In addition, Seate traces the histories of the “other” Aces, motorcycle bars and cafes that adopted the name, but were not otherwise related. Here is the US there were Aces in Chicago and San Francisco, both now closed. The first became a Starbucks, and caters to a different sort of coffee bar cowboy. Operating bars (at least at the time of publication) are also covered, especially the Fuel Café in Milwaukee.

In addition, Seate traces the histories of the “other” Aces, motorcycle bars and cafes that adopted the name, but were not otherwise related. Here is the US there were Aces in Chicago and San Francisco, both now closed. The first became a Starbucks, and caters to a different sort of coffee bar cowboy. Operating bars (at least at the time of publication) are also covered, especially the Fuel Café in Milwaukee.

There are problems. Despite some interesting quotes and observations, Seate doesn’t really delve deeply into his own research. For example, he asserts that record racing never happened (p.46-47), and yet only a few pages later he indicates a familiarity with Clay who asserts it did (p.54). According to Seate records then were shorter, three or four minutes. Kickstarts were too balky to get a racer going in time, let alone get a bike up to speed.

There are problems. Despite some interesting quotes and observations, Seate doesn’t really delve deeply into his own research. For example, he asserts that record racing never happened (p.46-47), and yet only a few pages later he indicates a familiarity with Clay who asserts it did (p.54). According to Seate records then were shorter, three or four minutes. Kickstarts were too balky to get a racer going in time, let alone get a bike up to speed.

Actually, pop songs today are still three to four minutes, hence the title of a Madonna single. Second, any rider who knows how and has a finely tuned bike (as café racers would), would get the bike going on the first kick. Clay has already covered route, speed, and gear changes. For Seate to assert record racing is nothing more than “an enduring myth”, he has to address contrary testimony, especially contrary testimony of which he would seem to be aware.

Seate also favors a breezy style, which, while easy to read, enforces that sort of shallowness. To his credit, the Ace is only notorious once (p.57). In addition, he’s fond of sprinkling the narrative with various Briticisms – bloke, trainers, bum in the air – but doesn’t always get them right. He uses café’d instead of caffed.

There is a marked disconnect between the photography and the narrative. Someone will be mentioned on one page, but the related photo will be several pages away. The most extreme example is probably Hugh Mackie of Sixth Street Specials here in New York. The photo appears on page 84 but Mackie and Sixth Street aren’t discussed until page 151.

There is a marked disconnect between the photography and the narrative. Someone will be mentioned on one page, but the related photo will be several pages away. The most extreme example is probably Hugh Mackie of Sixth Street Specials here in New York. The photo appears on page 84 but Mackie and Sixth Street aren’t discussed until page 151.

Despite the attempt to desensationalize the ton-up boys and weak production values, Café Racer is a solid snapshot of the community in the States.

With Mick Duckworth’s Ace Times (2011) we have the history of record for cafe racers and the Ace Cafe. Not only is the book sold through the Ace’s web site, but also Duckworth blogs on the site. In addition, Wilsmore, and his wife, Linda, are among the most quoted sources. Nevertheless, Duckworth has provided few answers.

For example, in his introductory notes, he says cafe – sans aigu – is “pronounced caffy or caff”. The book rigorously avoids the use of the aigu in the narrative. Yet there on page 10 is a picture of the Ace as it looked when it opened in 1930, an aigu flying proud.

While that was the photograph I remembered, there is a more interesting one on pages 14 and 15. It’s of the Ace right after it was bombed, the building mostly gone, but the sign, and aigu, intact against all odds, battered but unbroken. It was in the rebuild of 1948 in a streamline modern design that the signage was streamlined as well, and the Ace became aiguless. If it matters, the design was as prewar as the motorcycles then available.

Duckworth also suggests what might be the source of the “wrong Ace” photograph (p.269). “Not surprisingly, another cafe calling itself the Ace opened not far from the original on the A40 Western Avenue. Its proprietor Frank Leighton had been a customer at the original establishment and although some old stagers regarded the new Ace as an imposter, it attracted motorcyclists”. While I don’t mind the picture of Marianne Faithfull on that page, a picture of the new Ace would have been more useful in strict academic terms since it would confirm or deny that presumption.

He also does his best to clear up the issue of record racing. While noting in passing that it probably didn’t exist until the TV show aired (p.67), Duckworth nevertheless quotes Chester Dowling on the subject as saying: “We did cheat though … we chose the House of the Rising Sun (sic), a really long record”. The recording comes in at four and a half minutes.

He also does his best to clear up the issue of record racing. While noting in passing that it probably didn’t exist until the TV show aired (p.67), Duckworth nevertheless quotes Chester Dowling on the subject as saying: “We did cheat though … we chose the House of the Rising Sun (sic), a really long record”. The recording comes in at four and a half minutes.

As for the book itself, it packs more than 500 photographs into its 312 pages. Separate sections highlight the bikes of the 50s or 60s or how cafe racers dressed the part. The bike sections even include the nicknames various marques had: Trumpet for Triumph, Kwacker for Kawasaki. Curiously, Ennie for Royal Enfield is not mentioned.

The emphasis is on oral histories, about which Duckworth says in his introductory notes, “I can’t guarantee every story in this book is the gospel truth”. The problem with that sort of disclaimer is that it undermines the credibility of the volume.

The emphasis is on oral histories, about which Duckworth says in his introductory notes, “I can’t guarantee every story in this book is the gospel truth”. The problem with that sort of disclaimer is that it undermines the credibility of the volume.

Dave Croxford introduces the book, and keeps his section short. He even manages to refer to book. His connection to cafe racers is noted as are other famous people in the motorcycling world: Jim Higgens and RegPridmore. There is even a photographof a painfully young Mick Walker.

The narrative is well written though more colorful expressions in those oral histories are cleaned up. Here one does not take the piss, one extracts the urine (p.22). There is fun, but evocative, trivia: in the 50s, only 3% of the population rode motorcycles to work, as compared to 55% who walked or took a bus or train (p.30). Duckworth even provides the origin of the expression ‘doing the ton’ and connects two motorcycle films – The Leather Boys and Little Fauss and Big Halsey (both were directed by Sidney J. Furie).

But everything mentioned circles back to the Ace, or failing that motorcycles, whether it’s music, pirate radio, or the period advertising. (He covers the burn ups, the police baiting, the riots, the 59 Club, and media sensationalism as well.) It’s not enough that to know that Buddy Holly was popular among rockers. The reader learns that Holly bought an Ariel Cyclone, which was later owned by Waylon Jennings, who himself has no connection to the Ace.

But everything mentioned circles back to the Ace, or failing that motorcycles, whether it’s music, pirate radio, or the period advertising. (He covers the burn ups, the police baiting, the riots, the 59 Club, and media sensationalism as well.) It’s not enough that to know that Buddy Holly was popular among rockers. The reader learns that Holly bought an Ariel Cyclone, which was later owned by Waylon Jennings, who himself has no connection to the Ace.

This approach reaches a high point in an extended chapter on the hundreds of other transport cafes of the time. Here the reader gets a sense not of rockers being outside society but rather part and a product of the times.

The approach reaches a low point when at the end of an interesting piece reprinted from the King’s College student magazine. The bold face caption mentions that Derek Jarman was the art director. Jarman is indeed a bold-face name, but not in a history of a motorcycling subculture of which he was not a part.

Odder still is a section dedicated to the Wall of Death. It’s a legitimate part of motorcycling history even if it basically carnival sideshow stunt work. What, if anything, it has to do with cafe racers is never clearly explained.

The last section on the Ace revival is the most complete to date. While Duckworth glides over such analytic questions as to whether the local Council would have been so keen on preserving “our heritage” if there were no money to be made out of the past, out of nostalgia, he provides a clearer history of the exact sequence of events that lead to the reopening as well as the disasters that almost killed the dream.

If you are going to buy just one book about the Ace Café, café racers, and racing aces for your essential motorcycle bookshelf (a concept I’ll return to another time) the recommended choice is Ace Times. Mike Clay’s 1988 Café Racers would make a nice companion volume, though I hope you’ll pay closer to the £50 I did than the £200 that gave Seate sticker shock.

If you are going to buy just one book about the Ace Café, café racers, and racing aces for your essential motorcycle bookshelf (a concept I’ll return to another time) the recommended choice is Ace Times. Mike Clay’s 1988 Café Racers would make a nice companion volume, though I hope you’ll pay closer to the £50 I did than the £200 that gave Seate sticker shock.

Rockers! is a good and much more readily available alternative, if not the third book on your reference shelf (which is getting rather specialized). Seate’sCafé Racer would be next, since it covers the contemporary scene; and if you like then and now pictures, The Ace Café Then and Now would make a nice add on.

As for me, next October when I’m back in London I shall visit the notorious Ace Cafe, and, when no one is looking, lay a wreath to the fallen aigu. No records will be made, raced,

or broken.

Jonathan Boorstein

jonathanb@theridersdigest.co.uk

What a load of typicaly american (they cannot spell anyway) drivel. Us Brits started the caff racer in the late 50’s in more than one caff around Britain. There was also a group called the Double Zero Club in Birminghan (ours IS older than yours as well) that was also started by a reverand (David Coleyer). We have Greasy Spoons (roadside caffs) where motorcyclists and lorry drivers would stop for a bite to eat. (usualy a fry-up)

Did you read the first part of the book review Cyco? There are eight books reviewed in total and to the best of my knowledge Mike Seate is the only American author.

We may well have started the whole caff racer scene in the late 50s but let’s face it that was 65 years ago! As a reflection of the complete Ace Cafe, Café Racers, and Racing Aces scene, this in depth review is as definitive as it gets.