Whitchurch in Shropshire is one of those places that encapsulates the essence of Englishness with all its half-timbered houses, red bricks and stone-built churches. It’s a theme I want to explore with Paul Sample as his work seems to me quintessentially British, if not English. Having found my way surprisingly easily to a car park nearby I am soon knocking on the door of a solid, brick-built town house that is probably more ‘historic’ than it first looks. Paul himself answers the door, which shouldn’t surprise me as I wasn’t expecting a butler but it’s a down-to-earthness that immediately puts me at ease. He is a legend, after all…

He’s tall and fit looking and dressed in jeans and a dark blue shirt. He has clearly managed to avoid the seemingly compulsory habits and garb of traditional aging, which tend to afflict the generation slightly older than him. I’m led through to the kitchen, which is old and new at the same time, homely and a bit historic. It’s very British and I feel immediately welcome. Paul makes me a mug of tea and we sit at an elegant but substantial wooden table that is used rather than fussed over. Taking notes is too distracting and even I can’t read my handwriting after a day or two, so I set up my camcorder as it has a good microphone and four hours of recording; I can’t imagine being able to use all that up! “Oh, I can talk for hours if you let me,” says Paul, smiling. This is encouraging.

We’d already spoken on the phone and Paul had asked me to email him a list of questions, which he’d then not answered because we agreed a face-to-face would be so much better. I think it was a kind of test. And anyway, I told him I wanted to create a portrait of the man rather than ask a list of inane questions about Ogri. Nevertheless, I feel the need to maintain some semblance of professional detachment and impartiality rather than fall into the trap of just having a good old natter. I wanted to bring something of the man and his life out into the light.

So we start at the beginning, in Leeds on the 19th of February 1947 when Paul was born. His family moved to Harrogate when he was six and he says he used to have a very broad Yorkshire accent. He went to Rippon Grammar School and then at sixteen to Bradford College of Art to do a two-year pre-diploma. By then his family was living in Dewsbury.

I ask him when he knew he wanted to follow a career in art? “I didn’t, when I was fourteen I wanted to join the Navy because my father was the Second Engineer on a tramp steamer before the war and just as it started. In fact he was on one of the last ships to leave Singapore. He was then medically discharged for an infected arm injury and when he got home he became a draughtsman designing tanks.”

His father’s stories of the sea gave Paul romantic notions of wandering the oceans on a rusty steamship and the exotic mysteries of far-flung ports. Unfortunately he failed the Navy’s eye test so he had to think again. “I’ve always drawn, right from the age of four. I was always asking for paper to draw on and always, always drawing. So the school said why not go to art college instead?”

One of the tutors at Bradford was the now well known artist Patrick Hughes who, after looking at the new intake of student’s work said, “Right, you lot were probably born with a pencil in your mouth but this one here, Paul Sample, he’s been born with a silver pencil in his. He’s going to do well!” Paul was embarrassed by this but it was clear from the very beginning that he had talent.

After completing his two years at Bradford he then applied to the Central School of Art in London and whilst sitting in an antechamber with the other students waiting to be interviewed Paul was sketching away, as ever. The senior tutor came by, looked at what he was doing and said, “Well, there’s probably no point interviewing you – you’re in already.” Again, it was the immediate impact of the quality of his work and the fact that he was constantly engaged in it that was forging a path for the future artist.

The course was in graphic design but cartooning was a constant activity for Paul. “Even at grammar school I was always doing strip cartoons and caricatures of the teachers on my blotter, which were then confiscated.” Occasionally he got them back and they always had tea stains and other signs that they’d been widely distributed in the teachers’ common room. His last year at college was spent doing a six foot square painting of caricatures of all the students in a ‘London scene’, an effort he describes as “absolute crap,” preferring instead his smaller paintings and his sketchbook work.

At that time one of the visiting tutors was Roland Schenk, the Art Editor for the Haymarket publication Management Today. He noticed Paul’s work and offered to pay him £15 a time for small illustrations to accompany stories in the magazine, often three in one issue. “It doesn’t sound much but in those days £45 was a lot of money for a student,” says Paul. As his art school days came to an end he asked another tutor who was also a commercial artist how he might get more work. “I’m not going to tell you,” said the tutor, “you’re a threat to me getting my own work!” So off he went into the wide world with his portfolio under his arm.

Initially Roland Schenk offered Paul a job as a paste-up artist at Management Today, which was a skilled but not particularly creative position. Paul wasn’t keen and was even less so when he discovered the pay was £15 a week. Not that this was bad money but he reasoned that if it only took a couple of hours to knock out an illustration for £15 then why work all week for the same money! He decided there and then to become a freelance and set off round all the newspapers in London. He found work more or less straight away and produced illustrations for the Sunday Times, the Daily Mirror and as he puts it “the work snowballed from there.”

I ask Paul what it was like coming down from Yorkshire to London in the ‘swinging sixties’ as unfortunately I was too young at the time for all the sex and drugs; was it all it was cracked up to be? “I had a friend from college who was all into smoking spliffs and injecting heroin,” says Paul, ”but he ended up committing suicide by sitting on the railway tracks on the underground.” Before I can ask how this tragedy might have affected him Paul says with typical Yorkshire directness “I thought, ‘what a tosser’! I wasn’t into all that hippy stuff, I wore a leather jacket and jeans. And I bought a motorbike.”

This was Paul’s first, a Sunbeam, which he still has and turns out to be highly significant in the future genesis of his most famous creation. “It had a sidecar in those days,” says Paul, “I learned to ride on it and used it to go to college and take it down to the cafes.” On one occasion he ran out of petrol in the Aldwych tunnel and the police had to close it in the rush hour while young Mr Sample spent three hours looking for fuel. “Eventually I ended up at the Savoy and had to ask them where the nearest garage was.” Occasionally Paul would forget the sidecar was there and ram buses with it. He took it off after a while and rode the bike solo with plenty of spills and tense moments.

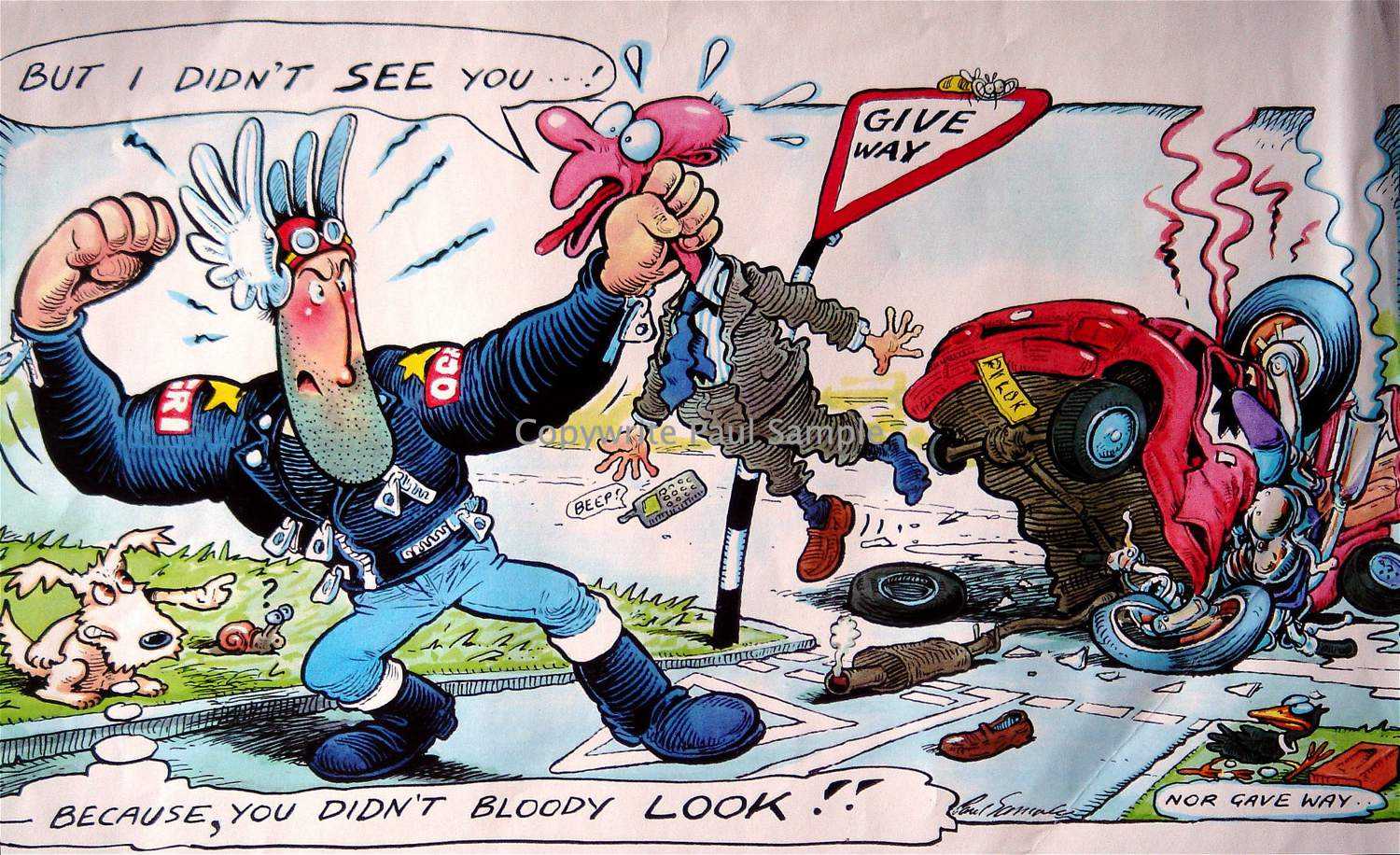

He then got a Triumph Thunderbird and the unscheduled contact with the ground continued unabated. “Tyres were crap in those days,” he says, “absolute crap! A bit of wet and you were off, every time.” On one occasion in the ice of winter he was sliding on his side past a taxi when the driver leaned out of the window and said, “You fucking prat… !” Any rider today would recognise the lack of sympathy and blatant hostility towards us bikers. I suggest to Paul that this was also fertile material for what was to become Ogri.

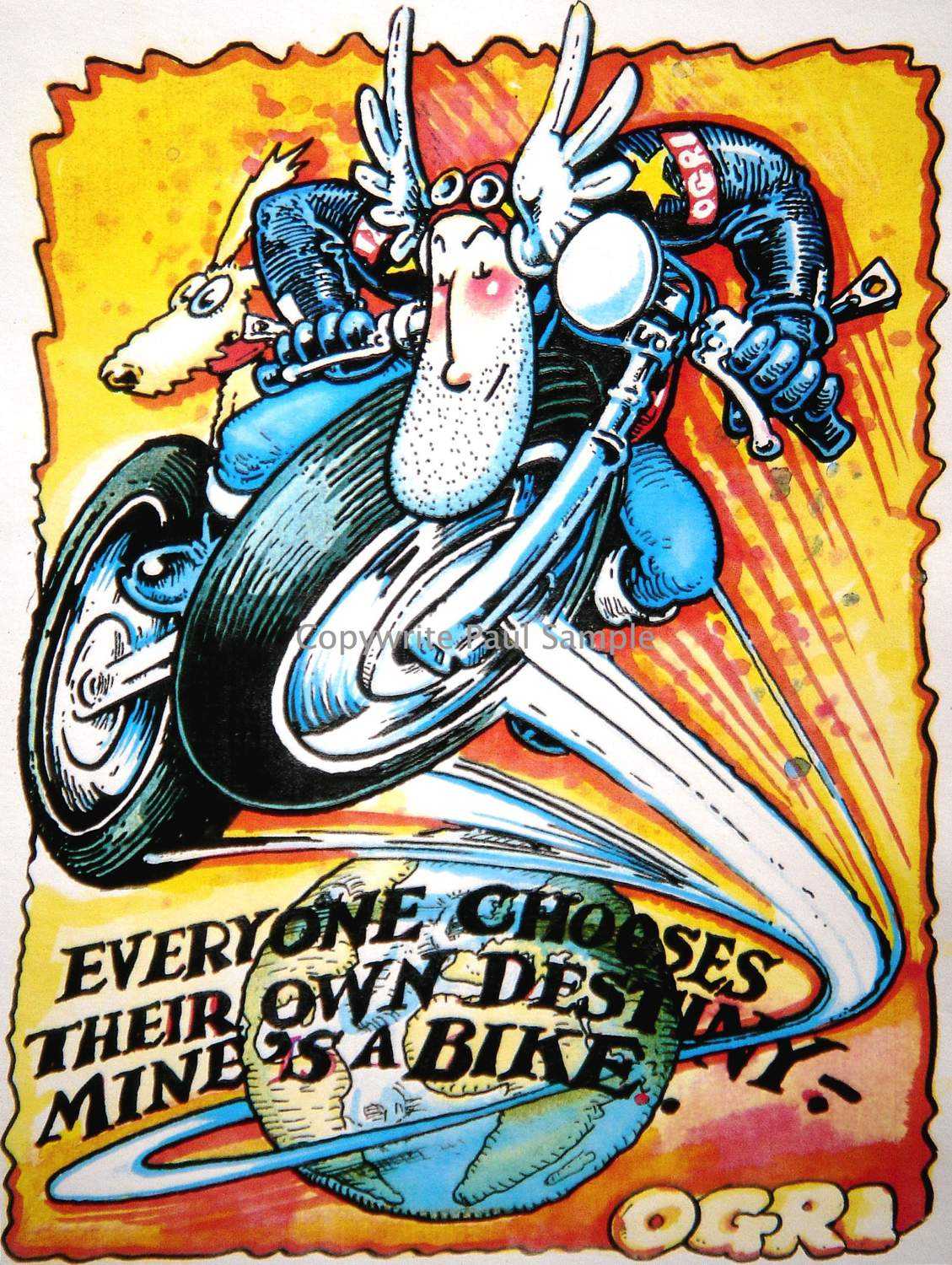

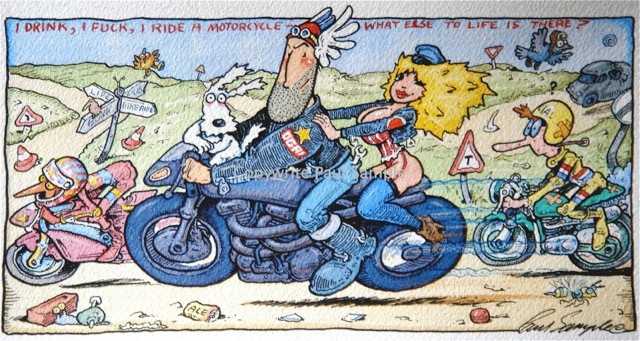

Indeed it did. “When I was still at college I started the idea of a strip cartoon and ‘Ogri’ was originally an exclamation used by one of the characters. I was into DC comics at the time and the Thor cartoon in particular. That’s where the winged helmet came from.” A lot of his biking adventures ended up as strip cartoons so he wouldn’t forget them. One day in 1972 Paul was doing some illustration work for Car Magazine and was told that a new motorcycle magazine called Bike was being created downstairs, and would he like to contribute any material. He showed them his idea for a bike-based cartoon strip, which they liked straight away. And in such brief moments history is made, lives change forever – not just Paul’s but ours, too.

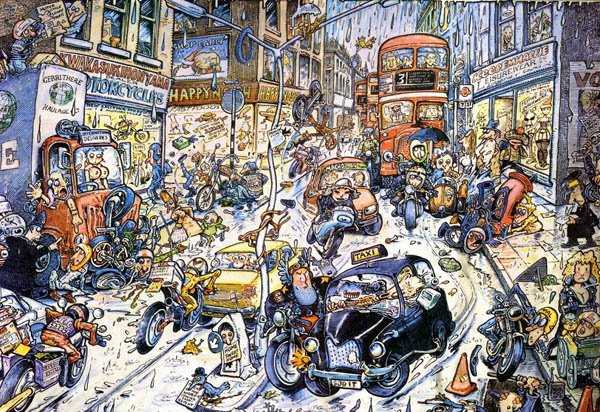

It seems impossible to imagine British biking life at the time (and for decades to come) without Bike magazine and Ogri. Any biker over forty will have it in their DNA and it had the same impact as having only three TV channels in creating a national shared experience. Every biker you met would be able to recall what was in that month’s issue and Ogri was ‘the’ bikers’ cartoon. It spoke not only to us but about us.

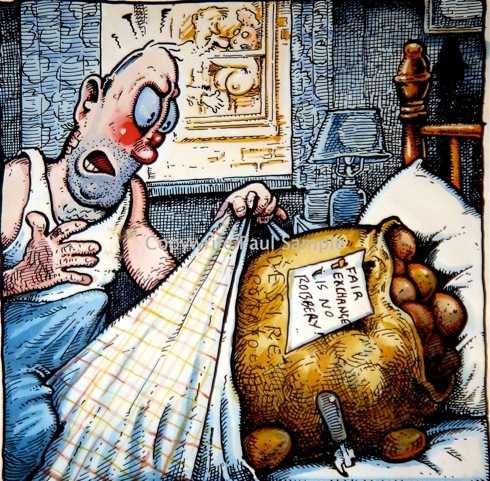

Paul continued to pour his own experiences into the strip and in the early days the narrative was more about Malcolm than Ogri. This touches on another of the questions I’d put to him in my email: how much of Ogri is the real you and how much is he someone you’d like to be (or not)? “Ogri is always the hero, the one everyone identifies with or wants to be,” says Paul, “Ogri does the things you’d like to do but would never get away with, like beating the shit out of a traffic warden and chaining him to a parking meter. But the Malcolm character is based almost entirely on me – and another friend. I was always getting everything wrong on the bike, we both were, so I’m Malcolm, really.”

On one occasion whilst blatting up the motorway at 90mph Paul heard a terrible rattle from the engine and just stopped, not knowing what to do and totally paranoid about blowing up the engine. True to his word, when this story appeared in the cartoon the protagonist was Malcolm not the eponymous hero. Later on whilst racing a Jag on the motorway Paul really did blow the pistons on his Thunderbird so he replaced it with a BSA Rocket Gold Star. I’m not convinced that’s what Malcolm would have done…

During his time at Bike Paul did some work with Bob Godfrey, the animator who produced Roobarb for the BBC. Godfrey said Paul was a natural animator and so I ask him if it was something he’d ever wanted to pursue with Ogri? “Yes, well I did do an animation…” Paul pauses and sucks heavily on his roll-up, “Gurgh, this is a story…” Having suggested the idea to his publishers EMAP they immediately put up £30k for a five minute pilot and Paul picked a studio whose team were all in to bikes to produce it. He wasn’t entirely happy with the result but he had control of the script and chose lots of rock music for the soundtrack. However it was good enough for EMAP to promise another £2m for a series of ten minute animations for TV and the commissioning editor at Channel 4 gave Paul the green light to start work.

After six months of script writing and layout sketches he went back to Channel 4 only to find a new commissioning editor. “Ours was one of four projects on the table but the new editor just swept them all in to the bin!” Undeterred EMAP decided to produce a half hour feature version, which Paul hated. “They got in a couple of professional script writers and none of the original ideas were followed. It was awful,” he continues, “It is awful, dreadful…” He produces the offending VHS, an object he hands to me with palpable disapprobation. “I wrote all the background stories, you know, like the little sub-plots that appear in the cartoon strip. They didn’t use any of them.”

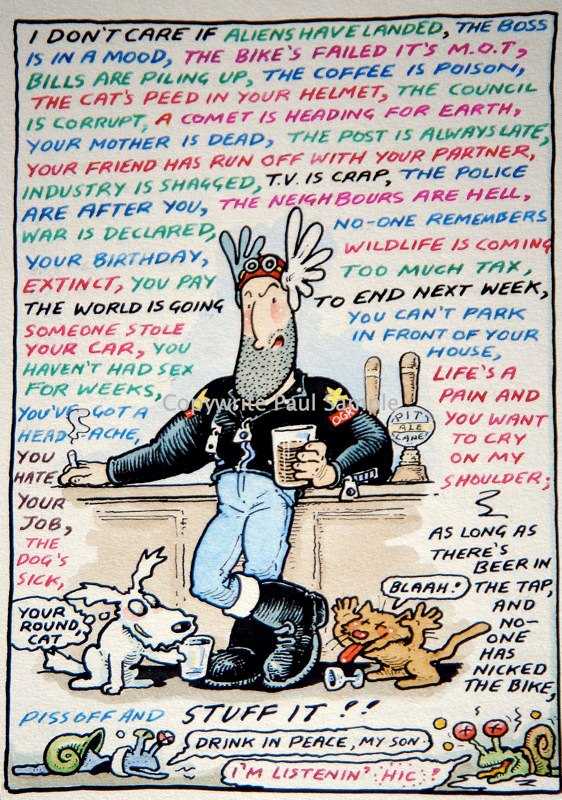

This neatly raises another one of my questions, namely: what part do all the little mice and snails play in your work? “They appear as I’m drawing,” says Paul, smiling. “It takes me about a week to do the whole strip and once I have the basic idea I write it as a film script. Then I break it down into frames, sketch it out and start to ink it in.” It takes so long to do the final drawings that the ideas for the sub-plots just come to Paul while he’s working. “They’re never scripted, they just happen and by the last frame they’ve developed into a complete story in their own right.” I have always felt that real genius is easily distracted because such minds are capable of coping with multiple layers of narrative and incorporating them effortlessly into their work. For me they are the bit’s of Paul’s work I like best; they are often surreal but equally seem to speak to the hidden lives of lesser mortals like us.

I ask if he was surprised by the success of Ogri? “I was a professional illustrator,” says Paul, “back in the eighties I was doing so much work I often didn’t know what day of the week it was. I had the illustrator’s paranoia, which was thinking the job you’re doing at the moment is the last one you’re ever going to do. I always had work but never turned a job down.” To start with Ogri was just a bit of fun as magazine work was less stressful for deadlines. However, as it developed Paul could afford to turn down some of the other work and concentrate more on Ogri. He knew it was a success when Dunlop approached him to use Ogri to advertise their Red Arrow tyres and the bosses at EMAP objected. After some very high level negotiations EMAP won the day but it cost them double what they had been paying Paul up until then. Some time later the bean counters suggested Ogri was costing too much so Paul stopped doing it for two years. When Roger Willis became editor of Bike he approached Paul to come back for the same rate, index linked, of course! “I asked him why they wanted Ogri back,” says Paul, “and he told me that magazine sales had dropped by nearly 40% since he was gone.”

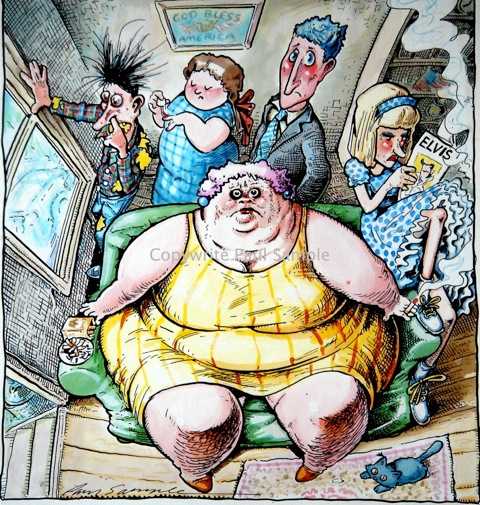

After Willis left Paul often clashed with later editors about themes in Ogri not being ‘politically correct’ or the fact that Mitzi was too scantily clad to be safe in case of an accident. “It’s not real,” Paul told them, “it’s a strip cartoon!” After a while he got fed up with it and when Bike magazine was taken over by Bauer the bean counters finally won the day and Ogri was axed. However, the strip appeared in the Sunday Telegraph motoring section for five years where the editor regularly received letters from ‘old generals’ saying how much they enjoyed it even though they weren’t into bikes. And that’s the secret of its appeal: it’s not really about bikes, it’s about life. And to this day Ogri lives on in Back Street Heroes magazine.

By now the interview has indeed turned into a good old natter and eventually we get round to the subject of Britishness. Paul emphatically regards himself as British rather than English. I ask if he’d ever considered living abroad? “I did think about living in France and went over there once in a Morris 1000. We went to Brittany and it was like driving in the 50s but no, I couldn’t live abroad. I haven’t seen all of this country yet and I’m running out of time,” he says smiling, “I haven’t been to Northumberland yet!” Paul says he likes going abroad “sort of” but he hates flying. He recently had a short break in Madrid but that was because he wanted to see two paintings in the Museo del Prado: The Garden of Earthly delights by Hieronymus Bosch and one by Breugel.

I ask if he has any hidden talents, other things he likes to do. “Painting,” he says, “and I’m really good at procrastination!” Unbeknownst to me the camcorder has run out disk space and switched itself off. We discuss many other things and discover a mutual loathing for Mrs Thatcher and her government. It’s the one time where I abandon any pretence at professional detachment and our loud enthusiasm for the topic brings Paul’s partner into the kitchen where she promptly joins in the fun. I also discover he served fifteen years as a parish councillor, dealing with tree preservation orders and combating the stodginess of the other members who he refers to as “mostly farming stock”. He is a man of many surprises.

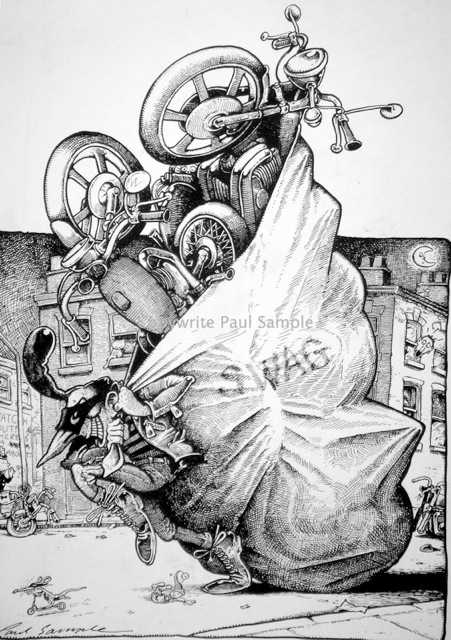

One of the things I haven’t revealed is how much we talked about bikes. You can take away Paul Sample the famous artist and what you’re left with is as complete a biker as you’re likely to meet. Every single crap, silly, fun or dangerous thing you’ve ever done on a motorbike he’s done too. This is why Ogri appeals so much, it hits the spot with bikers because it’s grounded in real motorcycling life and exaggerated just enough to make it art. Paul currently has his old Sunbeam, a Royal Enfield, a 1938 P&M 250 Red Panther to restore and an early 60s AJS 350. He’s planning to get a current Triumph Bonneville T100 in black and has had so many other bikes we’d definitely need another complete article to cover it all.

Regrettably I must go home but before I do Paul takes me through the house to see some of his paintings: one is a series of caricatures of English judges he did whilst at college, another is something he’s been working on for many years, a composition of bucolic scenes from his life, a church and fields and little groups of significant people. The house itself turns out to have had a new front added in the Georgian era, concealing a timber framed building from 1620. It all adds up so nicely, I feel I have been shown the roots of a magnificent oak.

Had Paul’s eyesight been better at the age of fourteen then one could speculate that we may never have seen Ogri or any of Paul’s other work but somehow I doubt it. One can make wrong turns in one’s early career but true talent always surfaces in the end. Not even Paul Sample could have stopped himself becoming a national treasure. It’s an awful cliché that I hate and having met Paul I know it’s a description he wouldn’t like, either. But equally, I can’t think of a reason why it isn’t true. His illustrations have reached so many corners of our lives not just in biking. You’ll have seen them on book covers and in magazines, in advertising campaigns and Christmas cards and newspaper articles. They are everywhere, often simply signed P. Sample.

Paul’s work says something about us Brits in the same way that Spitfires and Eccles cakes, and crankcases leaking oil do. It’s only by meeting him that one can pull all these different elements together in his most famous creation. Ogri isn’t an All American Superhero or a titan of Greek mythology. Don’t be fooled by his Desperate Dan chin and winged Helmet, he’s uniquely British. He’s a synthesis of Yorkshire grit and stubbornness, 60s biker culture, native cynicism and wit. He’s a rebel but also a pragmatist and a loyal friend. After only four hours with Paul Sample I realise that the part of himself he sees as Malcolm is only a fraction of the truth. How curiously charming it is that he can’t see how much of Ogri is also him.

Oldlongdog